Galleries, Games and HCI – Dan Howard

In this blog post I will be looking at how my readings in HCI have affected my overarching research interests and goals. Starting with a brief outline of my background, this post will introduce my interests in engagement in museums and galleries and game design with a number of challenges that I face in my research.

Moving from here I will discuss three aspects of my HCI reading, ambiguity, participatory design and experience-centred design. With a particular emphasis on the configuration of design processes, I will discuss each topic in turn and the potential implications that each of the areas of HCI research may have on my research interests.

Lastly I will argue that these three HCI design principles and methodologies have strong implications for how I will configure the design and making processes in my digital civics research. I will also demonstrate that the use of games and game design are of benefit to participatory and experience-centered design in HCI, concluding with a number of interesting areas for future research.

In doing this I hope to properly capture the relationships between my research interests, digital civics and HCI. I hope to unite all three, with a particular emphasis on the importance of process in facilitating learning and engagement, as a continuous strand throughout.

Background

As a starting point, my particular research interests in digital civics[1] are rooted in my experiences working in learning and engagement in galleries and from my passion and background in games and game design. Through my work in promoting young people’s engagement in contemporary art at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, I began to use games and game techniques to explore and promote experimentation in art and learning within exhibition contexts, with some success.

I became interested in how technology could be used to connect audiences with the learning opportunities provided by museums and galleries, and in questions such as how can communities work with museums and galleries in the curation and creation of learning experiences? And what role can HCI and games play in this?

Museums and Galleries

Cultural venues are extremely significant resources for learning and education. From museums to contemporary art, dance centres to theatres, they play a crucial role as centres for knowledge, cultural or otherwise. Many of them possess large archives and libraries, these are often open to the public, but woefully underused.

However, visits to cultural venues are not only motivated by learning opportunities, venues also act as social spaces, spaces for entertainment and reflection. Cultural institutions spend inordinate amounts of money in trying to understand their audiences with audience development companies such as Morris Hargreaves Macintyre. This leads us to ask, how can we use this knowledge to better engage people in learning in museums and galleries? What processes can we use within cultural venues that may allow us to capitalise on audience’s mixed desires for education and entertainment? One answer might be found in games.

Games in galleries

Games as a method of engaging audiences in museums and galleries have a good heritage in interaction design papers[2] [3] and there exists a number of higher profile examples of more public implementations such as Capture the Museum and ArtHunter. Many of these attempt to ‘gamify’ in a very superficial and non-meaningful way[4] the museum and gallery experience by augmenting it with artificial scoring systems and collection mechanics. This leads me to ask what is missing from these attempts to engage people, and can the answer be found in HCI?

This question was further compounded by my involvement in a number of ‘participatory’ projects (one of which can be viewed in the video below) where, acting as a game design consultant working with artists, I designed games that would facilitate participatory processes and group discussions. These experiences led me to the belief that design processes have their own important outcomes in terms of participant engagement, outside of any end product.

(skip to 1:55 for the good bit)

HCI

The challenge then for my Digital Civics research is threefold.

- How can we better design for engagement in museums and galleries?

- How do we configure our design processes so that they facilitate learning and engagement?

- What roles can games and game design play as a mode of engagement?

In my readings, I feel that HCI offers a number of potential answers to these questions. These can be found in the discussions around ambiguity, participatory design and experience-centered design.

Ambiguity

It is no surprise with my background working in learning in a contemporary art context that I was drawn to the ideas expressed by William Gaver et al in their 2003 paper[5] Ambiguity as a resource for design. As someone very experienced in encouraging debate and interpretation around vague and nebulous concepts, I found Gaver et al’s call to view ambiguity as a valuable resource for promoting engagement, comforting and uncontroversial.

Defining ambiguity as ‘a property of the interpretive relationship between people and artefacts’, the authors provide a well-structured, Swiss-army knife of design techniques that, when used properly, deliberately provoke ambiguity and vagueness. The series of techniques fall under three broadly defined forms of ambiguity, all of which leave particular aspects of a design or interface open to interpretation from the user.

- Ambiguity of information – where the meaning of presented information is unclear, leading to questions around trust and adoption.

- Ambiguity of context – where the context and presentation of an artefact itself is unclear, leading to questions around usage and intent.

- Ambiguity of relationship – where the morality or value of an artefact is unclear, leading to reflections around our own experiences and moralities.

The argument is that these ambiguities are important tools for design as they naturally lead to open and interpretative thinking, where users of a design must supplement with their own knowledge and beliefs.

For Gaver et al, this is extremely useful as it allows designers to pose questions or suggest issues, without imposing solutions. This frees up users to be critical or accepting, positive or negative, within a determined design space, making it valuable in raising questions and provoking responses.

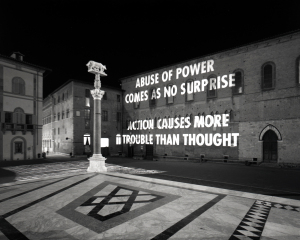

In terms of digital civics, ambiguity may have value not only by facilitating a better quality of response from participants, but also by increasing the appeal of, and therefore the engagement with, a design. This can seen in the Projected Realities[6] project outlined in Gaver’s paper, where the ‘mystery’ surrounding public electronic displays of ambiguous images and slogans promoted viewer’s engagement with an artefact.

Of course these ideas have a long heritage in contemporary art (see Jenny Holzer), but that does not stop ambiguity being a useful design tool for digital civic engagements outside of this context. It would be fascinating to see how they may be applied to other aspects of civic engagement, particularly in cultural venues such as museums or science centres where ambiguity in presentation and interpretation is generally not encouraged.

Consider also the vast archives held by our libraries, museums and galleries many of which have been, are being and will be digitized. Traditional designs for these fantastic learning resources have focussed on the efficiencies of sorting, finding and categorizing, yet is seems clear from our discussion that the introduction of ambiguity in designs may lead to a much greater and more creative engagement and appreciation of these collections.

Linking ambiguity back to the questions raised around the role of games as modes of engagement, there are a number of studies that have used ambiguous game and game like elements in design and evaluation processes. Games frequently contain varying elements of ambiguity in their mechanics, and these have been used effectively in HCI, whether obfuscating the consequences of decisions made in order to elicit responses in participants[7], or using ambiguous simulation games to help shape user experience centred design[8]. Games and game like elements in design and design processes, are useful sources of ambiguity. They may help to focus the benefits of ambiguous design techniques in order to promote response and engagement from participants, users and co-designers.

Participatory Design

A crucial part of digital civics is working with local communities, organisations and governance to co-design new modes of service provision. Participatory design has an obvious role to play in this. Roughly conceived as design projects where the people destined to use a system also play a critical role in designing it, participatory design is a fairly well established design technique within HCI.

In Participatory Design: “Democratizing Innovation”[9] Björgvinsson et al sketch out a brief history of participatory design in HCI, tracking the practice from an early work based and ‘technocratic’ conception, to one that is increasingly focussed on all aspects of public life. They conceive the importance of participatory design not in the outcome creation of objects or things, but as a process in and of itself. A process that is intrinsically democratic. This idea is clearly supportive of the digital civics agenda as outlined above.

From their work with marginalised minority groups in two social innovation projects, Malmö Living Labs and Herrgårds Women Association, the authors discuss how creating spaces for constructive conflict in participatory design led to deeper and longer engagement from participants with projects, as well as supporting ideas of agonistic democracy[10].

What I find most interesting about this paper in regards to my research interests, is its focus on the process of design rather than the outcome. By attempting to shift the gaze of HCI from the production of new technologies (a trend the authors see as worryingly capitalistic) towards the configuration of design processes, it highlights one of the most valuable elements of participatory design. Namely that design and making processes can have valuable learning outcomes in and of themselves, separate from any end product or service.

For Björgvinsson et al, this is primarily the creation of agonistic spaces which support “a polyphony of voices and mutually vigorous but tolerant disputes among groups united by passionate engagement.” If properly configured, the heterogeneous makeup of different groups involved in participatory design processes can engender a stimulating and engaging environment of mutual learning and debate. This naturally has positive implications for digital civics research and in particular in my own area of interest in museums and galleries.

My own experiences of participatory processes in contemporary art have often been worryingly lacking in diversity. Frequently participation is drawn from a very narrow band of art ‘insiders’ and socio-economically privileged groups[11]. In order to avoid being tokenistic, participatory processes must be well thought out, transparent and configured properly[12]. Therefore it seems important for my research in engagement in museums and galleries, to address these imbalances and ensure a plurality of voices in any participatory processes of designing or making.

Relating this back to questions around the roles that games play in engagement, we can see that many games create safe, participatory environments of conflict. This is particularly the case in games which utilise traditional board and card game mechanics. See for example Matthew Wood et al’s ‘Talk about Sex’[13] game, where a multiplayer participatory game that utilises turn-based card mechanics is used to create a safe space for young people to discuss issues around sex. If designed properly, games can encourage and promote dissensus and conflict by being essentially competitive.

Yet a ludic design space could potentially minimize social issues that may arise in normal participatory design processes. For example, turn-taking mechanics allow everyone to have a say in a structured format without worrying about some people being too dominant. Additionally games could be seen as creating ‘artificial zones of conflict’ where it is safe to express differing views and contrasting opinions in the spirit of the game, where in normal design processes people may not feel comfortable expressing opinions due to social factors such as wanting to please designers or experts, or going along with majority opinion.

Experience-Centred Design

Experience-centred design in HCI is a design philosophy that focuses on the experiential relationships that people have with technology. As a progressive and humanist approach, it reconceptualises users of technology away from the more ‘scientific’ understanding of traditional HCI practice and towards a holistic experiential understanding. Peter Wright and John McCarthy in their book Experience-Centered Design[14] credit the rise in popularity of this design philosophy to the general ‘turn-to-practice’ in third-wave HCI and the shift in focus from workplaces to the domestic and leisure spheres.

Tracing the evolution of experience-centered design from simply thinking in terms of usability and ‘end users’ to scenario-based field methods with iterative prototyping, to Scandinavian participatory design processes, the authors also express a meaning of experience heavily inspired by John Dewey’s pragmatism, one that defines experience as an irreducible and actively constructed act of sense making.

The idea here is that our experiences are more than our bodily actions and thoughts in the world, but that they are constructed by ourselves, co-constructed with others, that they are always emotionally connected to situations and that they are always in flux. Every experience is dependent upon an infinitude of factors and histories and can only be properly understood in that full context.

This approach has obvious implication for my research into engagement in museums and galleries. As stated previously, visitors are motivated to come to cultural venues for many different reasons and for many different types of experience.

An experience-centred design approach could provide a good methodology to inform design processes for this complex sector. Additionally, by viewing the designer and user as co-creators of experience and emphasising people as actors, socially constructing their own experiences and those of others, we are interestingly close to the ‘creative process’ as expressed in the way that artists in any field create for an audience. When considering the ways in which film makers, photographers, curators, choreographers, poets and authors design for the experience of their audiences, this approach seems a natural fit for the creative and cultural sectors.

How does this relate to games as a method of engagement? Well, much like the other creative disciplines as cited above, game design is fundamentally the curation of the experience of players. Pretty much all good game design starts from the core question of ‘what experience should the players have’ the answers to these questions then inform every design decision from that point. Game design is also an intensely iterative process, prototypes and play tested over and over again against the core ideals of experience centred design.

Game design then may provide then a useful tool in understanding and practicing experience centred design. In applying game and game like elements to design processes, we can use them to accurately co-create, curate, and capture the experiential relationships that users have with the results of our designs and with the design process.

There is a small amount of literature that explores the roles that games can play in understanding user experience in HCI[15], so I think this is a potentially interesting area for future research. As a method of engaging people in design processes, games and game design are, as already discussed, useful tools for creating safe, fun and participatory spaces that generate response and debate from users. It is worth investigating that they may also act as tools for understanding and shaping experience.

Conclusion

Relating these discussions back to my original three challenges for research, I believe that a lot of the reading I have undertaken in HCI has begun to provide some answers. In particular, my readings around notions of ambiguity in design have led me to think more closely about how engagement in museums and galleries could be promoted through the different types of ambiguity, be this in the end results of a design project or in the process of making and designing itself.

Participatory design has a solid history in HCI, and the discussion around its potential benefits and the debate around the importance of its configuration have led me to reflect upon my own experiences of participation in a cultural context. My readings around the essentially democratic nature of participation will greatly inform how I shape participatory processes in my research.

Lastly, experience-centred design offers a humanistic and holistic view of the experiential relationships between designers, artefacts and people that is closely in tune to my own philosophical orientation and design sympathies. It offers an approach to design methodologies that will undoubtedly influence my practice going forward.

In terms of my digital civics research, possible areas of future research informed by these readings could be into the effects of properly configured participatory design in the context of cultural institutions. Many institutions are unaccustomed or even resistant to agonistic processes, so I think this would be an interesting area of potential conflict to investigate.

However, it is my research interests into the use of games and game design elements as HCI processes, that has been most fomented by my readings. The potential for games to be used as method in participatory design in creating safe spaces of contest is an area of potential research. Furthermore the direct parallels between game design and experience-centred design lead me to propose that more investigation into the potential benefits of game and game like processes in experience-centred design, would be an equally if not more fruitful area of future inquiry.

References

[1] Patrick Olivier and Peter Wright. 2015. Digital civics. Interactions 22, 4: 61–63. http://doi.org/10.1145/2776885

[2] Anton Berndt. 2011. Playing the Museum: towards a rationale for games in exhibition design. Ie 2010. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2078109

[3] Tanguy Coenen, Lien Mostmans, and Kris Naessens. 2013. MuseUs. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 6, 2: 1–19. http://doi.org/10.1145/2460376.2460379

[4] Scott Nicholson. 2012. A User-Centered Theoretical Framework for Meaningful Gamification. Games+ Learning+ Society: 1–7. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_1

[5] W.W. Gaver, J. Beaver, and S. Benford. 2003. Ambiguity as a resource for design. SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems, 5: 233–240. http://doi.org/10.1145/642611.642653

[6] Gaver, W., and Dunne, A. (1999). Projected Realities: Conceptual design for cultural effect. Proc. of CHI’99 (1999), ACM Press.

[7] Regina Bernhaupt, Astrid Weiss, Marianna Obrist, and Manfred Tscheligi. 2007. Playful probing: Making probing more fun. INTERACT’07 Proceedings of the 11th IFIP TC 13 international conference on Human-computer interaction: 606–619. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74796-3

[8] Karin Slegers, Sanne Ruelens, Jorick Vissers, and Pieter Duysburgh. 2015. Using Game Principles in UX Research. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’15: 1225–1228. http://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702166

[9] Erling Björgvinsson, Pelle Ehn, and Per-Anders Hillgren. 2010. Participatory design and “democratizing innovation.” Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, Ehn 1988: 41–50. http://doi.org/10.1145/1900441.1900448

[10] Carl Disalvo. 2010. Design, Democracy and Agonistic Pluralism. Proceedings of the Design Research Society Conference 2010: 366–371.

[11] David Beech. 2008. Include me out! Art Monthly, 315: 1–4.

[12] John Vines, Rachel Clarke, and Peter Wright. 2013. Configuring participation: on how we involve people in design. Proceedings of the … 20, 1: 429–438. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-694X(98)00026-X

[13] Matthew Wood and Gavin Wood. 2015. Talk About Sex : Designing Games to Facilitate Healthy Discussions around Sex. 795–798.

[14] Peter Wright and John McCarthy. 2010. Experience-Centered Design: Designers, Users, and Communities in Dialogue. Morgan and Claypool Publishers.

[15] E H Calvillo-Gámez, P Cairns, and A L Cox. 2009. From the gaming experience to the wider user experience. Proceedings of the 23rd British HCI Group Annual Conference on People and Computers: Celebrating People and Technology: 520–523. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1671078

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.