Personal informatics vs. social imperatives

This paper [1] outlines a model of engaging with personal informatics systems (PIS) as a five-stage psychological process. Personal informatics systems are defined as “those that help people collect personally relevant information for the purpose of self-reflection and gaining self-knowledge”.

The model was derived from surveys and interviews with 68 participants who were already self-tracking on a regular basis. The five stages are: preparation, collection, integration, reflection and action. At each stage users can encounter barriers to using the system and the authors discuss how using their model could improve diagnosis, assessment and prediction of problems in PIS as well as informing design guidelines for such systems.

Of all the reading I have done so far for this module this is the paper that I have found most provocative. I can appreciate that modelling users’ psychological processes is an important part of designing personal informatics systems and has a long tradition within HCI. However, I am surprised that you can build a model like this with survey data from just 68 participants and by interviewing 11 people over instant messenger. The phrase “we did not determine a coding frame beforehand; instead we identified themes from the data as we processed the responses” raises questions about what analysis method is being employed here: is it Thematic Analysis? Grounded Theory? Or something else?

I also found myself questioning the authors’ individualist focus and I admit to being rather influenced by having previously read Deborah Lupton’s work in this area [e.g. 2]. She frames ‘self’-tracking as social in various ways. Firstly, and in my opinion most importantly, she argues that “self-tracking as a phenomenon has no meaning in itself. It is endowed with meaning by wider discourses on technology, selfhood, the body and social relations that circulate within the cultural context in which the practice is carried out”.

Self-tracking is also social in the sense that many self-trackers see themselves as part of a community of trackers and they share their personal informatics online and offline. In addition, personal informatics are being introduced into many areas of social life and social institutions for example when workplaces offer wearable technologies to increase physical activity amongst their employees (see here for some examples with discussions of the pros and cons from an information officer perspective [3]).

I come to the issues of personal informatics (or self-tracking) with potentially conflicting perspectives. As someone who is always interested in the political, cultural and social processes that influence any phenomenon I am probably inherently critical of work that ignores these processes. However, I am also someone who uses self-tracking as a way of self-managing chronic health conditions.

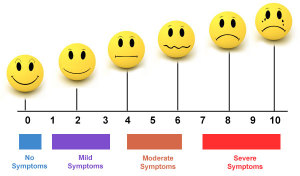

Therefore for my further work this week I was keen to see how personal informatics has been used to self-manage chronic pain. I could not find any ACM papers which addressed this issue so I have linked to this EPSRC-funded study [4]. While I am very interested in the problems addressed by this paper I do feel that it still frames some information as ‘objective’, for example, information obtained by sensing devices, in opposition to the ‘subjective’ reporting of pain levels.

One of the most interesting findings was that participants (people with chronic pain) wanted the PIS to provide “physical evidence of pain”. They even spoke of wanting a “transparent body that could be read and understood by themselves and others to foster acceptance and overcome stigma”. For me this highlights what Lupton calls ‘the valorisation of data’. I would argue that these concerns with making the invisible visible are the result of social, political and cultural pressures to be healthy, productive and working. People unable to fulfil these societal demands and functions are required to prove that they are not shirking and are thus entitled to the ‘sick role’. The participants were therefore hoping that the data provided by the PIS could aid social acceptance. However, my critical position is that data and PIS alone can never do this and we should always be wary of demanding too much objectivity from our socially produced and socially understood data.

Sources

1] Core reading: Li, I., Dey, A., and Forlizzi, J. A stage-based model of personal informatics systems. In Proc. SIGCHI 2010, ACM Press (2010), 577-66.

2] Lupton, D. Self-tracking cultures: towards a sociology of personal informatics. In Proc. OzCHI 2014, ACM Press (2014), 77 – 86.

3] Examples of company wellness schemes from chief information officer perspective

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.