Using Toolkits and Participatory Design to address issues within Digital Civics

Introduction:

Within this blog post I aim to discuss two main areas of Human Computer Interaction which I previously investigated throughout the module. Firstly, I will begin by explaining my own personal background and research interests with pervasive technology and engaging with rural communities. From this point I will be discussing how the emergence of technological toolkits has impacted on digital civics research as well as investigate how participatory design has influenced my own personal research interests. By developing the research on these two themes further, I intend to demonstrate the real-world practical benefits that can be achieved when carrying out research ‘in the wild’ [1]. In summary, my goal is to clearly express what links have been forged between my own research interests and practices as well as the research of HCI.

Background:

Prior to studying at Newcastle University I was heavily engaged with a number of local charities and held a variety of volunteering positions. Through some of my volunteering positions I was given the opportunity to teach and present which led me into my first degree of ‘Computer Studies and Secondary Education’ at Sunderland University. The degree allowed me to understand what teaching encompassed as well as gain a deeper insight into technology and programming, a subject that I had firstly studied at A-level. I found that the course although not strictly computer science, successfully stimulated my imagination allowing me for the first time to truly appreciate the full potential of computers, technology and programming. With my personal interests now refreshed and re-awakened, I wanted to focus on exploring computer science further. Consequently I decided to enrol onto a Masters in Computer Science course with Newcastle University which is where my research interests really started to develop.

Computer Science:

Delving into the world of computer science honed my programming skills in a number of different languages but it also introduced me to HCI as a research field. It was at this stage in my studies I was made aware that HCI had progressed far beyond graphical user interface design (GUI) with a more citizen-led approach to design outside the workspace within the real world [2]; a somewhat foreign idea for me at first as I had always assumed it was an ‘experts know best’ attitude (Mind set of a 1980’s HCI researcher?). At this stage in the course, I was also made aware that the introduction of new technology did not have to be extravagant or overly engineered to be effective. It can be simple, light and easy to integrate into real world use; characteristics which I felt were effortlessly demonstrated within PosterVote [3] when I first read the publication mid-2015.

Situated Displays:

As part of my dissertation project I was given the opportunity to work within Open Lab. The aim of the project was to create a network of situated displays within the context of a rural community.

Research conducted by former Open Lab researcher Nick Taylor et al. was used in the design of the physical system [4,5,6] as well as investigating how the displays could be made sustainable, remotely accessible as well as stable.

Situated displays have a range of inherent problems associated with them including display and interaction blindness [7]. They are ubiquitous parts of our society and are consequently severely overlooked as an effective means of information visualisation and communication. Looking back I realise that my approach used off-the shelf technology that is widely available to anyone. This led me to consider the effectiveness of such ‘toolkits’ and re-evaluate the direction of their focus within UbiComp. How can toolkits benefit my own research with situated displays as well as the wider context of digital civics research? My analysis will explore the physical links between toolkits and digital civics.

Working with Rural Communities:

As part of my work with situated displays I was given the opportunity to work alongside a charitable trust (GGT) and representatives of local government. Drawing from my previous experience of working alongside voluntary and charitable organisations I designed the situated displays with a fair amount of input from the stakeholders, however calling it an attempt at ‘participatory design’ would be an overstatement. On reflection, I believe the design process could have benefited immensely by taking a more participatory approach now that I understand what the method entails. With the planned continuation of a similar project in my MRes and possibly my PhD, I will identify a number of areas in which participatory design can be used to yield a more effective outcome by overcoming issues surrounding trust and relationships as a digital civics researcher.

What are the challenges?

My MRes project aims to continue working on situated displays alongside rural communities, local government and local organisations. Within digital civics there are a number of challenges presented that I believe HCI research can help overcome:

- How can we use toolkits to empower citizens within rural communities?

- How can participatory design be used to more effectively correspond with rural communities?

- To what extent can participatory design be used to streamline the process of building relationships and trust?

- How can participatory design bridge the knowledge gap when designing with rural communities?

Moving beyond Weiser’s vision:

Mark Weiser, the ‘forefather’ and visionary of ubiquitous computing has had an important impact on the direction of UbiComp. He coined the phrase ‘calm computing’ which took the basic principle of ubiquitous computing and told it to “stay out the way” so that it would serve the purpose of bringing people serenity, comfort and awareness of their surroundings in a non-obtrusive way. He correctly predicted that technological devices of the future (today) would be used for much more than work related activities. Within today’s society, people often own more than one device such as a smartphone, tablet, laptop or a desktop computer. They are still used for work purposes however they now extend far deeper into people’s lifestyle and are used for socialising, playing, communicating, searching and organising.

Although UbiComp has tended to follow along with Weiser’s vision, it has come under scrutiny somewhat by the likes of Rogers [8] who identified a string of ‘failed’ UbiComp projects. Roger’s asserted that Weiser’s theory was outdated and impractical as a result of these failings instead placing the blame heavily upon our implementation of artificial intelligence and lack of understanding about human nature. As I stated within my blog post [9], I agreed with Rogers on her interpretation of the current situation – we simply do not understand our own human traits enough to efficiently design technology that can interpret our sporadic behaviour. Instead, Rogers suggested that UbiComp take on a new approach by putting effort into designing toolkits for citizen-led ubiquitous design, based on the success of early software toolkits [13,14]. The use of toolkits would facilitate creative authoring, designing, learning, thinking and playing by providing both physical and digital sandboxes for a truly open and accessible experience. The concept of toolkits was touched on when examining UbiComp however the concept of Calm Computing took precedence at the time. Since then, toolkits has been further examined within the exploration of tangibles [11] where I realised they shared thematic parallel.

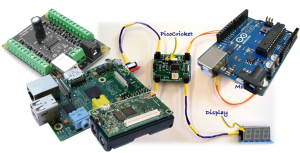

I believe that it is important to draw on UbiComp’s shift in focus as it serves as a reminder to one of the core principles of digital civics which is using technology to empower citizens. Toolkits such as ‘PicoCrickets’ [10], Phidgets [15] and Motes [16] are early examples of purpose built, rapidly configurable packages designed for children and adults alike that offer a wide range of add-ons ranging from sensors to programmable microcomputers. Aside from UbiComp, citizens can also access off the shelf hardware with which they can customise and adapt to their own creative tastes; examples include the Raspberry Pi and Arduino [11]. The key attraction of toolkits is their affordability. Due to the falling costs in manufacturing and technology throughout the years what was once seen as a premium piece of equipment that only few could afford and use can now be distributed widely to the mass population. Toolkits effectively hand over creative power to citizens by harnessing localised knowledge and experience instead of using academic knowledge as a starting point (‘experts know best’) – an alternative means for prototyping if nothing else [12].

Within my personal experience of using the more widely available off-the-shelf toolkits (Raspberry Pi), I successfully created a network of situated displays with 10 currently active within the rural community of Glendale. The toolkits enabled me to create a financially sustainable system which was used for information visualisation and distribution. Local authors (citizens) were given the authority to commission content for display through a digital platform which was in keeping with the motivation of digital civics. Looking ahead, I believe the lessons learnt from UbiComp toolkits can be further applied to my MRes project in developing a display commissioning service by adapting the core principles of affordability, rapid construction as well as easy customisability [12].

At present, toolkits appear to be strictly limited to hardware and software packages. In the near future I would expect to witness the development of toolkits which can be used for service design and prototyping within local communities and councils. In this context regarding my own MRes project I aim to setup a display commissioning procedure with local government in the form of a technological toolkit designed with the intention of setting up such a service as opposed to designing an object. This I believe would be a most useful and creative asset which citizens could use to empower themselves. Some projects already exist in this area suggesting a trend towards creative empowering vehicles, for example, App Movement which provides a service/toolkit for commissioning mobile applications.

Taking a step back

As already mentioned, my MSc dissertation was concerned with designing a network of situated displays for a rural community. I firstly explained how the physical toolkits that stemmed from UbiComp, can be used to empower citizens; now I will explain how the lessons learnt from participatory design could help improve the process of building relationships, rapport and trust when engaging with rural communities – a continuation into my MRes project.

Participatory Design:

Participatory design (PD) or co-operative design is an approach which aims to actively involve all stakeholders within the design process of a project. The methodology originates from the Scandinavians who boast a strong history of research into user participation in systems development stretching back to the 1970’s (see, for example, Bjerknes, Ehn and Kyng, 1987; Greenbaum and Kyng 1991) [17]. Björgvinsson et al. outlined a historical timeline of PD, beginning with a technocratic perception leading up an inclusive practice which takes into account all aspects of public life [18].

Greenbaum and Kyng (1991) summarised how PD revolves around a set of ideals [21] which should all be met for optimum outcome:

- The need for designing with full participation from the users/stakeholders.

- The goal of enhancing workplace skills.

- Computer systems are used as tools.

- Computer systems are used as a means to increase quality.

- The design process is conducted as political process with conflicts (Björgvinsson et al.).

- The use of situation as fundamental starting point for the design process.

Within my earlier blog post, I argued that the application of constructive conflict as a tool for raising alternative questions was a unique idea but debatably occurred naturally when engaging with communities [22] when multiple stakeholders are involved.

As a well-established technique for engaging with people throughout the duration of a project, a link to its importance within digital civics can be established. Digital civics researchers work with local communities, organisations and government, often immersing themselves to gain an accurate and meaningful insight into their inner configurations. With this deep involvement and contact with citizens, the importance of good communication is of paramount importance. Techniques learnt from PD can be used to build relationships and rapport with participants, citizens and communities which, if done correctly, start to establish the critical characteristic of trust [19].

Trust as a characteristic of a researcher-participant relationship is built through time with consistent demonstration of ability, benevolence and integrity at both sides of the exchange [21]. The process is bolstered by discretely building rapport with the participants which will lead to a more fruitful outcome for the project [19]. The personal qualities of the researcher and participant also have an impact on the way in which a relationship progresses. Ideally, both should be punctual, reliable as well as transparent in how they conduct themselves to ensure effective information exchange. Ultimately, if all these qualities are adhered to, both researcher and participant(s) can benefit from an outcome which has been mutually agreed and designed which saves time and resources within the project timeline.

Building Trust – James Davis (07:45 – 12:50) [20]

Modifications of PD have also been explored such as the integration of empathy which was integrated specifically for the purpose of working alongside vulnerable adults [25]. The work demonstrated by Lindsay et al. described how they developed personally tailored design artefacts to facilitate “safe walking” by placing emphasis on an emphatic relationship between participants and designers [26]. In this context, Lindsay et al. explain how this modified approach to PD can be used to bridge the “gulf in life-experience” by opening discussion with participants to remove designers preconceived irrational perceptions of what might be considered “good design” for the user. This proved an effective means of carrying out PD with people who suffer from dementia simply as a designer cannot envision how the world looks through their eyes. Alternative models have also been explored which include the OutsideTheBox project which deals with autistic children which shows strong parallels to the approach taken to help people with dementia.

With my continued intention of work alongside rural communities and local government, I feel that embracing a participatory approach to designing a display commissioning system would allow me to build the necessary relationships with collaborators within the project to yield the optimum outcome. PD is an efficient method of collaboration which keeps all stakeholders ‘in the loop’ so that at every step of the design process there are no surprises and all involved are in agreement with the progress and outcome. PD aligns itself with the vision of digital civics by overcoming the misunderstood idea of academia producing knowledge to be consumed by citizens, businesses and government rather allowing citizens, businesses and government to co-produce, co-own knowledge and technology [23]. Nick Taylor offers great insight into his own experience of applying PD to a rural context [24]. Overall he records his experience as being effective and rewarding however it also came with the issue of eliciting negative feedback. PD is seen as the go-to method for approaching projects and in a sense, it seems somewhat expected as the standard approach to take when corresponding with stakeholders. Due to the nature of PD, the constant repetition of closely communicating and corresponding with stakeholders can be seen as an enlightening experience as new relationships are formed. It is important to be aware that in these situations individuals may be hesitant to voice concerns throughout the design process in case of halting momentum and they may withhold comments until the end of the project through fear of tainting the new relationship.

Conclusion:

In summary, I truly believe that the challenges I have identified within my own research can be helped with the application of the principles learnt from HCI research. However I should note that my understanding was not simply taken from the separate areas of participatory design and UbiComp toolkits. It was in fact pieced together upon discovering more about HCI as an area of research with which I could form my own conclusions and opinions, drawing parallels and establishing my own links between ranges of topics in research literature.

Toolkits are not an unfamiliar concept within the world of HCI, they have existed in a variation of forms throughout the years with their focus being dictated by the progressive HCI waves. I believe we are currently in the middle of a transition from third wave HCI to fourth wave. Ubiquitous toolkits have been explored and their capabilities exhausted with a lot of UbiComp toolkits being produced which generally have similar features to one another albeit some of the more niche and ‘out of the box’ concepts. In terms of my digital civics research, a possible direction of future research would be to draw inspiration from the shift in focus. Moving away from the tangible and hands-on approach to toolkits, I envisage investigating digital toolkits for ‘infrastructuring’ and instilling services such as that of a display commissioning procedure.

A lot can be learnt from the vast history of participatory design and its solid grounding within HCI. Because of the amount of literature surrounding its success, it strikes me as being the standard methodological approach which should, if possible, be taken when engaging with stakeholders in a project ‘within the wild’. At present, I view participatory design as a framework for which you then apply ‘bolt ons’ if needed, to better suit the context of your project. Examples of ‘bolt ons’ could be the introduction of empathy and to a certain extent conflict. It would be interesting to further investigate alternative models of participatory design that take a step towards alleviating negative feedback in such a way that it does not impact on the design process. As a design process however, it is unfamiliar to many institutions, organisations and communities and so if carried out effectively could yield a substantially better outcome than if it were not attempted. Yet another area for future research would be to investigate the effects of purposely causing conflict (as a technique) for the benefit of embracing a more inclusive design process. At present, I believe communities are only accustomed to conflict as and when it occurs naturally – this agonistic process could yield interesting results.

References:

[1] Carroll, J. M., and Rosson, M. B. Wild at home: The neighborhood as a living laboratory for HCI. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 20, 3 (2013), 16:1–16:28.

[2] Olivier, P., and Wrignt, P. Digital civics: taking a local turn. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. (2015), 61-63.

[3] Vlachokyriakos, V., Comber, R., Ladha, K., Taylor, N., Dunphy, P., McCorry, P. and Olivier, P. PosterVote: expanding the action repertoire for local political activism. In Proc. DIS 2014, ACM Press (2014), 795-804.

[4] Taylor, N., Cheverst, K and J. Muller, A_ordances and Signi_ers of Community

Noticeboards, 1st ed. Nara: Computing Department, Lancaster University, 2009, pp. 1-4.

[5] Taylor, N. and Cheverst, K. Social interaction around a rural community photo display.

International Journal of HumanComputer Studies 67(12), 2009 10371047

[6] Taylor, N., Cheverst, K.: \Exploring the Use of Non-Digital Situated Displays in a Rural

Community. In: Workshop on Public and Situated Displays to Support Communities”, 2008

[7] Huang, E. M., Koster, A., and Borchers, J. Overcoming assumptions and uncovering

practices: When does the public really look at public displays? Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2008,

228243.

[8] Yvonne Rogers. Moving on from weiser’s vision of calm computing: Engaging ubicomp experiences. In Ubicomp, pages 404–421, Orange Country, Ca, 2006. Springer Verlag.

[9] Nicholson, “Stuart Nicholson: Moving on from Weiser’s Vision of Calm Computing” 2 October 2015. [Online]. Available: https://openlab.ncl.ac.uk/hci-digitalcivics-2015/stuart-nicholson-moving-on-from-weisers-vision-of-calm-computing/. [Accessed 10 January 2016].

[10] Verner, Igor M., and Dan Cuperman. “Learning interactions with and about robotic models.” Proceedings of the 2014 ACM/IEEE international conference on Human-robot interaction. ACM, 2014.

[11] Nicholson, “Toolkits and Making – Stuart Nicholson” 2 November 2015. [Online]. Available: https://openlab.ncl.ac.uk/hci-digitalcivics-2015/toolkits-and-making-stuart-nicholson/. [Accessed 10 January 2016].

[12] Grenhalgh et al., “A Toolkit to Support Rapid Construction of Ubicomp Environments” [Online]. Available: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?rep=rep1&type=pdf&doi=10.1.1.217.5558. [Accessed 10 January 2016]

[13] Myers, B., User interface software tools, ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), Vol 2, No 1, pp 64 – 103, 1995

[14] Roseman, M., Greenberg, S., Building real-time groupware with GroupKit, a groupware toolkit, ACM Transactions on computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), Vol 3, No 1, pp 66-106, 1996.

[15] Greenberg, S. and Fitchett, C. (2001) Phidgets: Easy Development of Physical Interfaces through Physical Widgets. Proceedings of the UIST 2001 14th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, November 11-14, Orlando, Florida, p209-218,ACM Press.

[16] System architecture directions for network sensors, Jason Hill, Robert Szewczyk, AlecWoo, Seth Hollar, David Culler, Kristofer Pister . ASPLOS 2000, Cambridge, November. 2000

[17] Bødker, S (1996). “Creating conditions for participation: Conflicts and resources in systems design”. Human Computer Interaction 11 (3): 215–236. (Reference 5 in participatory design wiki page).

[18] Björgvinsson, E., Ehn E. and Hillgren P., Participatory design and democratizing innovation, Proc. PDC 2010, 41-50, 2010.

[19] Le Dantec, C. and Fox, S. Strangers at the gate: Gaining access, building rapport, and co-constructing community-based research. Proc. of CSCW’15.

[20] Davis, TEDx Talks,. Building Trust | James Davis | TedxUSU. 2014. Available via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9FBK4eprmA. [Accessed 11 January 2016]

[21] Bødker, S., and Halskov, K. Participation: basic concepts and research challenges. In Proceedings of the 12th Participatory Design Conference: Exploratory Papers, Workshop Descriptions, Industry Cases-Volume 2, ACM (2012), 149–150.

[22] Nicholson, “Participatory Design and ‘Democratising Innovation’” 20 October 2015. [Online]. Available: https://openlab.ncl.ac.uk/hci-digitalcivics-2015/participatory-design-and-democratising-innovation/. [Accessed 10 January 2016].

[23] Goddard, J. and Valance, P. The University and the City. Routledge, London, 2014.

[24] Taylor, N., & Cheverst, K. (2008). This might be stupid, but…: participatory design with community displays and postcards. In Proceedings of the 20th Australasian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction: Designing for Habitus and Habitat (pp. 41-48). New York, NY: ACM.

[25] Stephen Lindsay, Katie Brittain, Daniel Jackson, Cassim Ladha, Karim Ladha, and Patrick Olivier. 2012. Empathy, participatory design and people with dementia. Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’12: 521. http://doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2207749

[26] Meißner ,“Empathic Participatory Design as a Cure for Reductionism” 20 October 2015. [Online]. Available: https://openlab.ncl.ac.uk/hci-digitalcivics-2015/empathic-participatory-design-as-a-cure-for-reductionism/. [Accessed 10 January 2016].

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.