Dementia: Drawing Parallels between HCI and Digital Civics

Introduction

Throughout the course of the module I have considered how my readings in the wider area of HCI and digital civics relate into my own research interests of technology in later life and dementia. There are many parallels in HCI and digital civics on the area. Dementia very much falls under the digital civics research agenda as research here looks to preserve agency and help increase quality of life. Following on from this much research in HCI has implications for dementia research, especially concerning the notion of ageing in place. This post focuses on three areas of digital civics and HCI, where applications of these areas to dementia and technology in later life are discussed. The areas concerned are participatory design (PD); tangible and embodied interaction (TEI); and pervasive computing.

Within participatory design I will explore how a Scandinavian practice led structure has changed in response to the third wave of HCI, and how application of an experience led approach has allows for meaningful PD with vulnerable people. I’ll be questioning how we can evaluate these PD processes, taken from frameworks presented in HCI, to help better configure future PD approaches. I will be discussing how the field of TEI has been used within HCI and how it can expanded on to suit a digital civics agenda, looking on how creating feelings of nostalgia help to reconnect with those who have dementia and preserve agency. Lastly I focus on pervasive computing within HCI and its application to digital civics. On this subject I ask questions of how what I have seen in my readings of ethical and consent issues propagate into my research interests within digital civics, and how this could affect research of ageing in place.

Participatory Design

HCI has long taken a Scandinavian practice based approach to PD since it inception in the 1970’s. In my readings of HCI I came across the works of Bødker who questions how we consider practice within participant’s workplaces (Bødker 1996) to gain a better understanding of our participants needs, to how PD can be moved forward into the third wave of HCI (Bødker 2006), and even a case study into practice based PD outside of the workplace (Bødker et al. 2014). I find PD to be particularly interesting as its bottom-up approach allows us to gain a much better understanding of our collaborators needs than what a typical top-down would allow. Using PD we can quickly build technologies better suited to collaborators, that are likely to have a larger positive impact, and are hopefully more sustainable as collaborators have designed it with researchers.

However within this approach to PD is very much practice based, where we work with collaborators to help improve the completion of a task, whether in the workplace, or with Bødker’s suggestions, in the home. Yet this doesn’t translate into research where often there isn’t a task that needs improving, such as communicating with vulnerable people or helping to create assisting technologies. This normal PD approach would also be difficult to implement in groups where there are varying needs of each individual, preventing artefacts being generalised out to wider groups.

Within digital civics I have found literature which aims to help configure PD to a digital civics agenda, tailoring towards older people and those with dementia in particular. Lindsay et al.’s research in PD for those with dementia builds on from Bødker’s points on bringing PD into third wave HCI, but instead moves from understanding practice to experience. Lindsay et al. tackles this through applying thematic analysis to workshops transcripts in order to help share a lived experience with those who have dementia (Lindsay et al. 2012). This is furthered from Lindsay et al. (2012)’s practical guidelines in how to conduct PD workshops with older people which can be used in conjunction with the previous research.

Lindsay et al. shows how research taken from HCI has been adapted and specialised to serve those with dementia, yet the configuration process is now much more difficult as experience is likely to be influenced by stakeholders in the project. This approach to PD requires greater consideration in identifying those who impact the research so true given experience can be extracted, for example showing care not to mix caregivers thoughts with those who have dementia (Lindsay et al. 2012). Research in this area aims to clarify what it means to configure participation (Vines et al. 2013), allowing us to identify who are the stakeholders in these projects and how outcomes differ across all parties involved. Understanding how our PD processes are configured allows us to undertake effective evaluations for workshops and outcomes, enabling modification of these configurations for more effective future approaches.

Lindsay et al. (2012) noted the importance of evaluation when conducting PD with those with dementia, stating the constant need for evaluation following each workshop allows us to ensure these PD process preserve a shared understanding of participants experiences when working within dementia. Drawing from my readings in the wider HCI area Bossen et al. (2016) tackles what it means to conduct an effective PD evaluation in the paper: ‘Evaluation in Participatory Design: A Literature Survey’. The authors do this not for a dementia based agenda, but to contribute to the question of whether PD enhances workplace quality, democracy, mutual learning, and empowerment; moving back into a practice based approach, yet their findings still apply when conducting evaluations. Yet the parallels between these research focuses are obvious, as experiential and practical PD both strive for mutual learning and sustained positive changes. Bossen et al. approach this question by conducting a literature survey of 143 papers categorised into: relevant (66) and irrelevant (77) papers. These papers were sourced from PDC 1990 – 2014, including special issues from the PDC website featuring some papers from CHI and CSCW.

Bossen et al. first define their interpretation of evaluation, stating a difference between qualitative and quantitative evaluations but focus on the former. They state evaluations can focus on: input, implementation, output, outcome, and impact; but an evaluation that focuses on one will be entirely different to an evaluation focusing on another. Within these areas the authors base their meta-evaluation on questions of ‘Who conducts the criteria?; ‘For which purposes?’; and ‘Based on which criteria?’. Using these the authors develop a collection of 7 questions which they can use to analyse evaluations in PD projects.

Although the evaluation review works from a small set of papers, a final group of 13, their guidelines of what a good evaluation should follow is well defined and acts as a great framework for deciding whether a particular PD was effective. Within experiential based PD this is something I see as extremely valuable as needs and experiences of collaborators, especially in a dementia context, are so nuanced that a really effective evaluation is needed in order to build from it. Bossen et al. notes most evaluations are conducted by researchers but certain types of evaluation, namely impact, may benefit from a participant led evaluation as they would be best placed to observe the impact. This is something mirrored in the PD process conducted by Lindsay et al. where participants were greatly enthusiastic with the solutions they were presented, having the greatest impact on them in increasing their freedoms of independence, but this view wasn’t entirely shared by other stakeholders such as caregivers. However it could prove difficult in allowing those with dementia to evaluate the PD process, taking from Bossen et al. (2016)’s suggestion of allowing participants to evaluate, as the nature of the condition may inhibit evaluation of long term impacts.

Participatory design is a technique that can be configured for a variety of applications with great benefits of mutual learning and giving voice to participants. Approaching PD from an experiential process is something I feel helps preserve agency, especially when used with vulnerable people. As seen with Lindsay et al. (2012)’s research voices may fade in the shadow of caregivers or illness but in taking time to understand their experience and design this into solutions brings these voices back into the forefront of thought.

Tangible and Embodied Interaction (TEI)

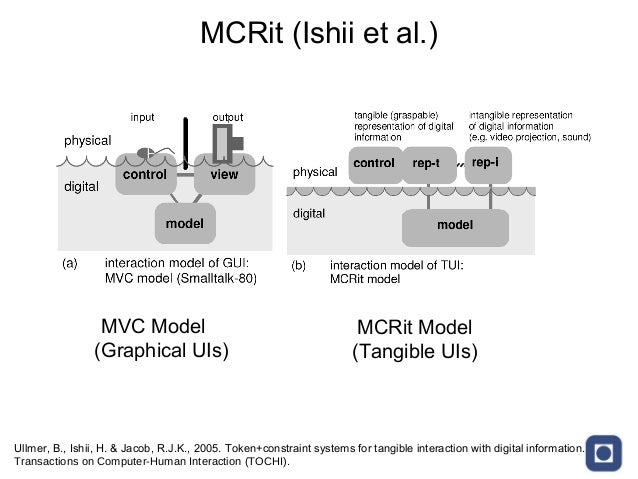

I found TEI’s alternate paradigm on what it means to use a computer captivating. I found TEI moved away from the regular input/output paradigm of computing, as seen in graphical interfaces, by combining these input and output through a form of physical embodiment. This physical embodiment allowed users to manipulate data in TEI systems through physical or gestural actions. When viewing this with a lens on dementia I thought there to be vast uses in helping with engagement and education, but also as discussed below what it can achieve in terms of preserving agency.

Within what I’ve found from a digital civics perspective the ‘Digital Jewellery’ project uses personhood to help preserve agency in those with dementia (Wallace et al. 2013), this is achieved with bespoke digital jewellery, created through an experience-centred design process. This project applies TEI to create jewellery that allows those with dementia to interact with their own memories through the embodiment of a digital representation of said memory as jewellery. Although Wallace et al. would not describe Digital Jewellery as a TEI it is the embodiment of memories in these artefacts which defines the interaction. This approach takes the paradigm of embodied computing to create objects that invoke reminiscence within those with dementia and their family members. This process takes a similar view to van Dijk et al.’s research around embodied cognition in TEI but follows a more Situational approach as discussed by Gaver et al. in their cultural probes work (Gaver et al. 1999). Distributing cognition through the embodied memories in the jewellery could help restore a certain sense of self through resurfacing forgotten memories and allowing the person with dementia to emotionally connect with those around them through the shared remembrance.

Although this very far from Ullmer’s PhD defence (Ullmer 2002), where he outlined the field through his work on Tangible Bits (Ishii & Ullmer 1997) there is much that can be applied from this to a digital civics perspective. At this early stage Tangible Interaction looked at how physical interaction with the computer can be used as an alternative when working with data aggregates (Ullmer 2002) and modelling, such as Urp (Underkoffler & Ishii 1999). A classic example of tangible interaction being the Digital Desk (Wellner 1993). These are some of the most early works in the field but give examples of how tangible interaction breaks away from the standard desktop environment by hybridising the characteristics of digital and physical interaction (Dourish 2004). Whilst this is root of TEI the argument can be made that Digital Jewellery doesn’t strictly fall under this banner, however works such as Digital Jewellery is much more akin to later research in TEI which I feel are much applicable to a dementia led digital civics perspective.

An example could be Manches et al. (2009)’s ‘Physical Manipulation: Evaluating the Potential for Tangible Designs’ examines the effectiveness of tangible technologies as a resource for educating children. This is approached by first evaluating the benefits and disadvantages of physical manipulation of data. Manches et al. discovers how physical interaction allows children to develop their own strategies for completing numerical tasks, stemming from the children’s familiarity with physical objects and the freedom of constraints placed on children from GUI designers. Building on this I think it could be interesting how a TEI approach could be used for intergenerational applications. In this context TEIs could be extremely useful in educating younger people in age-related conditions, especially dementia, and the implications of these conditions in such a way that can be much more readily understood.

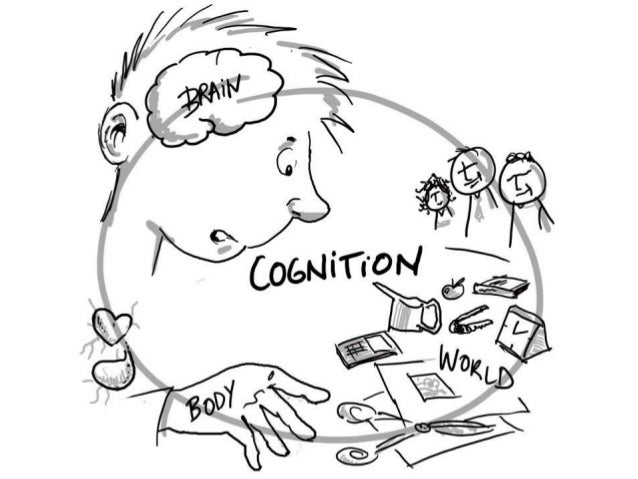

Another direction of TEI is van Dijk et al. alternative application of the earlier noted view of embodied cognition (EC) in their paper ‘Beyond Distributed Representation’ (van Dijk et al. 2013). van Dijk et al. explores the role of EC in TEI, looking at three different variations of EC, paying particular focus on distributed representation and computation (DRC). On this theme they explore how tangible interfaces based on DRC can reduce the cognitive load for the user through the context TEIs are placed

in. van Dijk et al. note how contextual cues can provide cognitive scaffolding, shifting the centre of cognition from the user’s thought processes to the wider environment.

This approach creates avenues into how the cognitive scaffolding created by EC TEI systems could be used in working with those with dementia. An example could be Wallace et al.’s empathy probes with how the tangible embodiment of a memory allows the person with dementia to re-establish their personhood and connect with those around them as the object could be said to provide much of the cognitive base of the conversation. However it can be difficult to incorporate EC into TEI systems even with guidelines from Hummels & van Dijk the systems still require such a precise environment which may not be effective when used with a degenerative condition such as dementia. These systems could be effective when designing for the individual as seen with ‘Digital Jewellery’ as noted earlier in the blog post, even this is extremely difficult to scale because of the focus on lived experience.

Ubiquitous Computing

The last area of discussion is that of pervasive computing, especially concerning consent in systems that look to aid ageing in place. This is an area I find particularly useful because of conflicts net in benefit and ethical responsibility. HCI applications of pervasive systems have often been used to monitor, whether for medical purposes, reassurance for family members, or something more akin to Weiser’s vision (Weiser 1991). As these systems fall further into invisibility and become more of a reality there are questions of whether our current models of consent are suited to such applications. I find this question to be particularly important, especially concerning the application of monitory pervasive systems on those with dementia. If those not suffering from degenerative illnesses experience difficulty in understanding what they are consenting to in these systems can we expect those who are to be able to give informed consent?

Luger & Rodden (2013) address the issue of consent in ubiquitous systems in their paper ‘An Informed View on Consent in Ubicomp’ (Luger & Rodden 2013) through a series of elite interviews. The authors question this issue of the suitability for traditional consent models in pervasive systems, and if deemed unsuitable, how consent should be approached. Commonly, a process of consent involves a user allowing a service to use their data as the service sees fit; this action would occur when the user first registers with the service and they would then not engage with the consent process again throughout their use of the service. The authors argue that this should not be the whole process of consent for ubiquitous systems, especially given the separation of user and service in pervasive systems, and also services that users would come to rely on in their daily actions.

Luger & Rodden’s interviews created two definitions for consent. Some saw consent as reducible to a contract, whereas, some took the view consent was a ritual form of protecting individual rights, freedoms, and one’s self. A key concern was of comprehension in a traditional consent model, stating that in the brief moment consent is addressed information is not conveyed effectively to the user. The researchers found a quarter of the experts they interviewed agreed that the traditional model of consent is not appropriate for ubiquitous systems and was in need of revision. Interestingly the researchers never consulted general users on what they thought of current models of consent, nor do they approach interviewees on their thoughts of consent in monitory pervasive systems. With a quarter of their interviewees deeming traditional consent models inappropriate I wonder whether this would be the same if the interview was directed towards more ethically challenging systems.

In context aware ubiquitous systems I think consent should be a key concern especially with the notion of such systems relying on our private data, mentioned in Rogers (2006)’s critique of calm computing and in Weiser (1991)’s Computer for the 21st Century. The authors put forward a framework of pushing consent as a social process, developing informing, designing for consent, and reconnecting user’s with their data. I think these are important things to keep in mind when designing monitory systems to aid ageing in place. I feel the goal of these systems is to prolong independence, where the first step is giving understanding monitory systems if an older person should chose to install one. I feel in doing this less sense of home is lost and allows for increased agency.

Conclusion

In conclusion over the course of current readings into HCI and digital civics I have found directed and related works towards for technology’s role in dementia. From looking at the areas of PD, TEI, and pervasive computing I have identified a large body of work that I can draw from in my future research but also something that has shaped my views on HCI, digital civics, and technologies for dementia.

The potential benefits of participatory design makes the approach something I am keen to explore into my own work. Its aspects of mutual learning and potential for increased sustainability is something I undoubtedly think will greatly influence my future work, especially in delving into experience rather than practice, in which I’ve tangentially explored through an internal discourse on Gaver et al.’s cultural and Wallace et al.’s empathy probes. This follows into my readings of TEI, especially on alternative approaches such as EC and it’s use in education. I think this coupled with more experiential approaches could help provoke more nuanced and novel exploratory technologies in my future research. Finally, a key concern of mine when working within the space of dementia in digital civics is that of ethics and consent, something I was able to explore vicariously through the theme of pervasive computing. Pervasive systems are something I’ve long had an interest in and are an area I’d like to explore in my research but this will undoubtedly be influenced through the questions raised in my recent readings.

References

Bodker, S. (1996), ‘Creating Conditions for Participation: Conflicts and Resources in Systems Development’, Human-Computer Interaction 11(3), 215–236.

Bødker, S. (2006), ‘When second wave HCI meets third wave challenges’, Proceedings of the 4th Nordic conference on Human-computer interaction changing roles – NordiCHI ’06 (October), 1-8.

URL: http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=1182475.1182476

Bødker, S., Klokmose, C. N., Korn, M. & Polli, A. M. (2014), ‘Participatory IT in semi-public spaces’, Proceedings of the 8th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction Fun, Fast, Foundational – NordiCHI ’14 pp. 765–774.

URL: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2639189.2639212

Bossen, C., Dindler, C. & Iversen, O. S. (2016), ‘Evaluation in Participatory Design

: A Literature Survey’, Participatory Design Conference pp. 151–160.

Dourish, P. (2004), Where the Action is: The Foundations of Embodied Interaction,

MIT, London.

Gaver, B., Dunne, T. & Pacenti, E. (1999), ‘Design: Cultural probes’, interactions 6(1), 21–29.

URL: http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=291224.291235

Hummels, C. & van Dijk, J. (2015), ‘Seven Principles to Design for Embodied Sensemaking’, Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction – TEI ’14 (figure 1), 21–28.

URL: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2677199.2680577

Ishii, H. & Ullmer, B. (1997), ‘Tangible bits’, Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems CHI 97 39, 234–241.

URL: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=258549.258715

Lindsay, S., Jackson, D., Schofield, G. & Olivier, P. (2012), ‘Engaging older people using participatory design’, Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’12 p. 1199.

URL: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2207676.2208570

Lindsay, S. et al. (2012), ‘Empathy, participatory design and people with dementia’, the 2012 ACM annual conference pp. 521–530.

URL: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2207676.2207749

Luger, E. & Rodden, T. (2013), ‘An informed view on consent for UbiComp’, Proceedings of the 2013 ACM international joint . . . pp. 529–538.

URL: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2493446

Manches, A., O’Malley, C. & Benford, S. (2009), ‘Physical manipulation: evaluating the potential for tangible designs’, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Tangible and Embedded Interaction – TEI ’09 pp. 77–84.

URL: http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=1517664.1517688

Rogers, Y. (2006), ‘Moving on from Weiser’s Vision of Calm Computing: engaging

UbiComp experiences’, Ubicomp ’06 pp. 404–421.

URL: http://www.springer.com/uk/home/generic/search/results?SGWID=3-40109-22-173677111-0

Ullmer, B. (2002), Tangible Interfaces for Manipulating Aggregates of Digital Information, PhD thesis, MIT Media Laboratory.

Underkoffler, J. & Ishii, H. (1999), ‘Urp: A luminous-tangible workbench for urban planning and design’, Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems: the CHI is the limit pp. 386–393.

URL: http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=303114

van Dijk, J., van der Lugt, R. & Hummels, C. (2013), ‘Beyond distributed representation’, Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Tangible, Embedded and Embodied Interaction – TEI ’14 pp. 181–188.

URL: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2540930.2540934

Vines, J., Clarke, R. & Wright, P. (2013), ‘Configuring participation: on how we involve people in design’, Proceedings of the . . . 20(1), 429–438.

URL: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2470716

Wallace, J., Wright, P. C., McCarthy, J., Green, D. P., Thomas, J. & Olivier, P. (2013), ‘A design-led inquiry into personhood in dementia’, Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’13 p. 2617.

URL: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2470654.2481363

Weiser, M. (1991), ‘The computer for the 21st century’, Mobile Computing and Communications Review 3(3), 3–11.

URL:

Wellner, P. (1993), ‘Interacting with paper on the DigitalDesk’, Communications of the ACM 36(7), 87–96.

URL: http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=159544.159630

Leave a Reply Cancel reply