EXPERIENCES OF YOUNG PEOPLE : Building a Bridge between HCI & Digital Civics

What is the Context?

When I think of the Arab Spring uprisings since 2010, I cannot not ponder on the idea that these movements were primarily led by frustrated youth who had the urge to break the oppression being exerted on them on daily basis through various formats and to amplify their voices. Zooming into Lebanon, a country with various existing tensions mainly driven by sectarian intricacies as a result of the civil war dated in 1975 and the political rollercoaster it has been through, youth in that country are a highly interesting group. In fact, within a population of 5.8 million, youth (defined as aged between 15 and 24 years old) [1] constitute 29 to 32% including Palestinian and Syrian youth whose numbers cannot be determined conclusively. In such a context, war memory narratives are continuously argued and re-appropriated to fit political agendas, interests of class and sectarian discourses [2]. According to Meskell [3] “Beirut’s “negative heritage” is a warning of the danger of memorializing shame, pain, and victimization”.

On the other side, when thinking about HCI, an eclectic field not necessarily clearly defined, that offers different approaches examining design and how humans might interact with it or inform it. Taking it one step further, is noticing how it translates into Digital Civics which heavily relies on linking design processes to civic matters. It is noteworthy to highlight that along both fields, a set of implications emerge related to participation, control, ethics, democracy, publics, experience and so on…and the actual challenge is to find out how all of these elements among others can work together, while taking into account existing tensions and creating meaning out of it all.

In line with all of the above, this blog post is an attempt to explore participatory techniques such as cultural probes and digital storytelling and how they translate into experience-centred design. Additionally, it will dwell on the implications of such techniques on democratising participation and perhaps fostering empowerment of youth specifically. And finally it will align all of those elements with the concept of public design and how it can all be linked to my own research interest which involves young people and the provocative heritage of Beirut that continuously influences young people’s narratives and identities.

Tell me about Cultural Probes

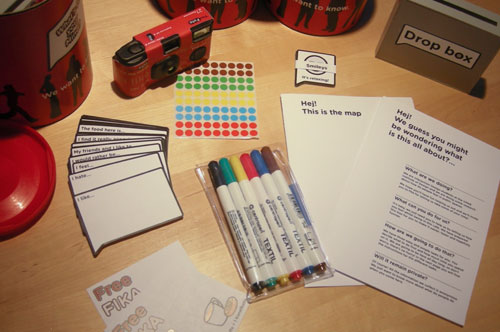

The work of Gaver et al. [4] explains cultural probes as an evocative set of tasks aiming to extrapolate significant responses from people. Those responses are not necessarily very comprehensive but rather bring together random/fragmented hints about the thoughts and lives of people. Cultural probes are usually adopted by researchers as a kit encompassing a camera, postcards with prompts and maps to highlight activities and relationships. This technique is used in order to inform design ideas for technologies enriching people’s lives in an innovative and pleasurable manner [Ibid]. As such probes reflect multi-layered experiences of people, triggering through observable facts emotional implications and realities [Ibid]. When examining cultural probes through the lens of the paper by Boehner et al. [5], it discusses issues such as the lack of documentation regarding the transition from cultural probes to actual design. Additionally, the paper mentions that several studies examine the uncertainty underlying cultural probes with scrutiny and tend to search for concrete meanings behind the responses of people. As a result they would rely on methods such as follow up interviews to collect further information to consolidate the rigor of cultural probes within HCI research methods. This shift from wider interpretation to a more focused one can be explained as a shift from the interpretation of what people expressed to the researcher trying to attribute people’s responses with clear cut facts [Ibid]. Consequently, it decreases the richness and surprise elements of cultural probes and further consolidates prior assumptions of researchers, defeating as such the essence of cultural probes. Hence, generalizability based on cultural probes is considered doubtful [Ibid].

Tell me about Digital Storytelling

As for digital storytelling, through its process, people create films which aim to amplify their voices; generating input to the public culture [6]. It balances between the ethics of democratic ‘access’ and aesthetics in order to maximize relevance and impact [Ibid]. The specificity of digital storytelling is that it relies on ‘vernacular literacies’; competencies and skills which are not exclusively related to artistic education but are rather acquired through every day experience and a result of being a mass media consumer [Ibid]. Through the use of digital tools of production and distribution, it combines communicative practices including telling personal stories, collecting and sharing personal images and textual languages of mass media; and transforms that mix into a publicly shared culture [Ibid].

Based on your experience, We will design for you

Having explained both techniques cultural probes and digital storytelling, it is important to examine how these translate into experience-centred design.

Dewey [7] defines experience as a relationship between the self which encapsulates personal interests and ideologies and the object. According to Wright, McCarthy and Meekison [8], experience encompasses four threads:

1) Compositional: examining the whole structure of an experience and the consequences and explanations of actions.

2) Sensual: examining the engagement with ‘sensory properties’ of a physical artefact or a technology.

3) Emotional: examining emotions attributed to an experience such anger, joy, satisfaction, fulfilment and disappointment among others.

4) Spatio-temporal: examining the unfolding of actions and events in particular time and place.

Acknowledging the importance of ‘Knowing the User’, HCI according to Wright and McCarthy [9] has made major methodological and conceptual progress in better understanding the user’s experience and research practices that accompany that. Based on the aforementioned aspects of experience and the earlier sections, when exploring experience-centred design, cultural probes are potentially among the primary way to understand the richness of people’s experiences [5]. By being provocative and engaging, they enable researchers to explore with people intimate, idiosyncratic and personal issues while being open enough for non-task oriented parts of the user experience [Ibid]. Similarly, digital storytelling which convenes a public representation of self fits well in examining challenging experiences of people [10]. Therefore, those techniques feed into the idea of conceptualizing and approaching people’s experiences and capturing these in the design process.

In this case, can we talk about Participation and Empowerment?

After exploring cultural probes, digital storytelling and how they can be used in experience-centred design, it is pivotal to ponder on all of that in relation to issues such as participation and empowerment.

Cultural probes were criticized by some for not being participatory enough since most of the control lies within the hand of the researchers [5]. In line with that, many suggest that the transition from probes to actual design ideas should be actively engaging participants. However, it is common to also find in the literature, researchers who contest the idea that cultural probes aren’t participatory enough as they infer participants a voice to reflect on their own experience and practices in a more enjoyable manner [Ibid]. Through reflection about their experience which resonates with Wright, McCarthy and Meekison’s framework [8] , participants acquire more control on the information they want to share and are free enough to have some ambiguity in their responses.

Along these same lines, digital storytelling is a cultural production challenging issues of access, self-representation and literacy and distinguishing between everyday experience as perceived by critics or artists and the experience that is depicted through ‘vernacular’ communicative means [6]. Nonetheless, participants who usually engage in such creative practices might not even be active in media cultures such as blogging and might not have used a computer at all in some instances which raises questions about the extent of engagement [Ibid].

Relying on such techniques suggests the democratization of technology in the sense of inferring more space for creativity and agency, leading to a surge in participation and productive leisure [Ibid]. Concurrently, Florida [11] claims that such ubiquitous creativity fosters cultural citizenship. Digital storytelling as an example for such creativity was indeed used to empower marginalized youth and communities by enabling them to create and share stories that consolidate their sense of social recognition, shared values, self-identity and self-advocacy [10].

Taking this one step further, one can dwell on the idea of democratising participation and how one can rely on such techniques to do so, by pushing researchers to go to the ‘wild’ and engaging with participants. This idea of researchers getting out of static spaces is visible in the projects conducted in Malmö Living Labs [12] where researchers explored ‘new milieus’ of participation and relied on innovative participatory techniques to optimize the engagement of participants .Yet, as Vines et al.[13] highlight, often creative participatory tools aim to support democratization and agency of usually disempowered people but they would often be taken on by those whose voices are most likely to be heard to begin with. Acknowledging this idea, it is necessary for researchers to embrace different forms of participation and to ponder on the idea of who is actually benefiting from participation [Ibid] and perhaps aim to accomplish some sense of ‘mutual benefit’ between them and participants, because it seems rare in HCI research to clearly reflect on the benefits for participants [Ibid].

Nevertheless, when exploring the potential of participation and extent of shared control, it is crucial to be aware that tensions and challenges might emerge and as such, techniques like cultural probes and digital storytelling through their reflective and perhaps therapeutic nature can infer a better understanding of these and how to account for them in research[10].

My Research Interest, Public Design & Everything Else

Having explored cultural probes, digital storytelling, experience-centred design and some implications regarding participation and perhaps empowerment, this is where I will be aligning these with the concept of publics and public design and link all of that to my research interest.

As stated in the introduction, the issue at hand is young people and the cultural/historical controversial heritage of Beirut among other cities of Lebanon. My interest is to understand how young people in Beirut who might be from different nationalities perceive the heritage of this city and its interplay with war narratives. The aim is to explore the lived experiences of those young people and how certain landmarks in the city would trigger certain narratives and emotions from their side. It is quite obvious at this point, that cultural probes and digital storytelling through their elements of ambiguity, vernacular communication and creativity would enable young people to explore challenging experiences especially that sectarianism is quite embedded in their daily lives and is quite sensitive as a topic. Additionally, because those techniques promote self-expression, self-advocacy and self-recognition, they are quite liberating. Consequently, all of that could fit into an experience-centred design which builds on these rich experiences and how they could be translated into a digital technology that genuinely captures those intricacies. Along those lines, this could be linked to the orientation in HCI towards the creation of publics and the emphasis on matters of concern.

Matters of concern as DiSalvo et al. [14] explain are situations and resulting consequences which form subjective experiences that translate into political conditions. The civil war in Lebanon along with all the political phenomena that occurred are matters of concern because of the tensions it created somehow found themselves engrained within communities without being always visible. For young people who are the current and future generations of the country, matters of concern as such need to be put forward because as DiSalvo et al. [Ibid] frame it, it is a necessity to engage with matters of concern from an experiential perspective and to devise tactics need that put forward these matters and act upon that. Taking that into account, as much as it might be challenging to tackle the intricate History of Lebanon and the subsequent tensions and to search for narratives that are often hidden in order not to disturb or to avoid engaging with sensitive topics, it is crucial as noted by DiSalvo et al. [Ibid] to articulate these problematic issues within design which in its turn should convey lived experience, apparent consequences and anticipated futures. Hence, these issues would be considered by a collective ‘public’ (a social entity which is formed to interact with the problematic issue) [Ibid] in this case, young people. The idea here is that when I think about my potential projects, I believe that I should be adopting a ‘public orientation’ especially that I will be examining a problematic topic which might not necessarily have a solution but exploring it in itself is interesting enough because of the dynamics it entails and the multiple understandings that could emerge from it which again resonates with what DiSalvo et al.[Ibid] mentioned “A public orientation takes a step back from the common design imperatives of providing solutions or initiating change […] the purpose of design becomes to identify the qualities and factors of a condition and make those qualities, factors and their relations experientially accessible”.

That is why, I find myself drawn to combine between the orientation of Public Design, Cultural Probes, Digital Storytelling and Experience-Centred Design with the aim not necessarily to find solutions for complex issues but perhaps to engage with participants in creating new meanings and re-imagining constraints and parameters that surround problematic issues as alluded by DiSalvo et al. [Ibid]. As such technology would be mapping out some of the existing realities, experiences and dilemmas and reshaping relationships through the lens of an agonistic perspective with participants included throughout the design process.

Some Final Thoughts…

Writing this blog post was quite overwhelming because it gathers different elements that might not be directly linked and tries to weave them together and figure out how they can work together in a harmonious manner. Exploring the different bits separately through the existing literature with some of the critique and flagging some of the issues that come along with these such as participation and empowerment has been a challenging exercise because most of the time these issues are not very evident. There might be some ambiguity in how all of these could operate together because some might argue that experience-centred design and public design for example cannot be linked , yet based on my readings and own interpretation, I can see that those two could work together because in order to design for publics , highlight matters of concerns and examine them more closely, one would need to rely on the experiences of this public and try to capture these through creative techniques with a genuine intent to benefit participants somehow while respecting some of the research demands and necessities. Moreover, when thinking about a concept such as empowerment, some might suggest that this is a bit far-fetched for techniques such cultural probes and digital storytelling. Yet, for me having explored these personally and checked how they could be implemented, one can sense a resulting empowerment, not necessarily by changing a young person’s life but rather but supporting this young person in acquiring skills that could enable him/her to break the silence, express strong emotions and perhaps ultimately dare to question some of the tensions that accompany matters of concerns and how these could be tackled in the future.

References

[1] United Nations “World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision”. 2015. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/ accessed on 15/12/2016

[2] Larkin C. Remaking Beirut: Contesting memory, space, and the urban imaginary of Lebanese youth. City & Community. 2010 Dec 1; 9(4):414-42.

[3] Meskell L. Negative heritage and past mastering in archaeology. Anthropological quarterly. 2002; 75(3):557-74.

[4] Gaver B, Dunne T, Pacenti E. Design: cultural probes. Interactions. 1999 Jan 1; 6(1):21-9.

[5] Boehner K, Vertesi J, Sengers P, Dourish P. How HCI interprets the probes. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems 2007 Apr 29 (pp. 1077-1086). ACM.

[6] Burgess J. Hearing ordinary voices: Cultural studies, vernacular creativity and digital storytelling. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies. 2006 Jun 1; 20(2):201-14.

[7] Dewey J. Experience and nature. Courier Corporation; 1958.

[8] Wright P, McCarthy J, Meekison L. Making sense of experience. In Funology 2003 (pp. 43-53). Springer Netherlands.

[9] Wright P, McCarthy J. Empathy and experience in HCI. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2008 Apr 6 (pp. 637-646). ACM.

[10] Clarke R, Wright P, McCarthy J. Sharing narrative and experience: digital stories and portraits at a women’s centre. InCHI’12 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2012 May 5 (pp. 1505-1510). ACM.

[11] Florida R. The rise of the creative class, and how it is transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life.

[12] Björgvinsson E, Ehn P, Hillgren PA. Participatory design and democratizing innovation. In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial participatory design conference 2010 Nov 29 (pp. 41-50). ACM.

[13] Vines J, Clarke R, Wright P, McCarthy J, Olivier P. Configuring participation: on how we involve people in design. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2013 Apr 27 (pp. 429-438). ACM.

[14] DiSalvo C, Lukens J, Lodato T, Jenkins T, Kim T. Making public things: how HCI design can express matters of concern. In Proceedings of the 32nd annual ACM conference on Human factors in computing systems 2014 Apr 26 (pp. 2397-2406). ACM.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply