No Big Fix: Digital Civics for Environmental Sustainability

Environmental sustainability is one, if not the key challenge of today’s world. Unsurprisingly, HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) research has been engaged with this issue, trying to find ways to meaningfully contribute. As I will discuss in detail, common approaches however try hard and often fail to find simple solutions to a very complex problem. In my eyes, the Digital Civics agenda, with its focus on participation, communities, and local contexts offers an approach that recognises the complexity at hand and wants to foster collaboration with and understanding among social groups active in the field. In this blog post I want to outline my personal take on the relationship between environmental sustainability, HCI and Digital Civics. The first section will present key fields that inform my approach to this relationship, whereas the second section will discuss ways to put it into practice.

1 HCI, Sustainability, and Planning

This section is structured into four themes that inform my understanding of Digital Civics for Environmental Sustainability. First I will discuss issues around common approaches in HCI to sustainability, which will then lead to looking at the role of urban planning. Consequently, I will look at two approaches and challenges to involving citizens in planning and design.

1.1 HCI and Environmental Sustainability

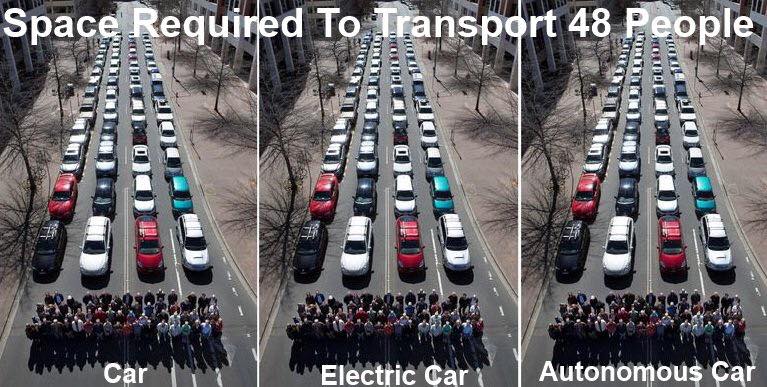

My interest in digital civics and urban planning is based on my concern for environmental sustainability. Before joining the Digital Civics programme in Newcastle, I researched (and criticised) persuasive technologies (Fogg 2002) that aim to make individuals aware of unsustainable energy (Figure 1) (Prost et al. 2015) and transport (Prost et al. 2014) behaviour and nudge them to adopt sustainable practices.

Criticism of such persuasive approaches has been substantial (Brynjarsdottir et al. 2012, Dourish 2010). Overall, they align with a modernist and colonialist approach to doing HCI (Dourish 2012). They follow a narrow definition of sustainability by using quantifiable data to measure it, an issue I will address in more detail later on. They also assume rational actors that base their decisions on a neoclassical cost/benefit model. Moreover, they are too distant from lived use and practices (Prost et al. 2015) as they ignore the complexity and messiness of everyday live that might make it impossible for inhabitants to live more sustainable. Finally, such approaches have a limited timeframe and it is unclear how change in the long-term can be achieved and how rebound effects can be addressed.

So instead of imposing solutions onto individuals, an approach that has been coined as solutionism (Morozov 2013), my motivation is to look at systemic issues around inequity of wealth and education, at infrastructures, at policies, and the planning system. This means for me to work both within system (with policy makers, planners) and with citizens (through community engagement, participation, and with activist groups) to improve environmental conditions in a local and specific context.

1.2 Planning & Public Consultation in the UK

The UK context of planning is particularly interesting for Digital Civics. On the one hand, as part of the localism legislation, central government handed over decision power and responsibilities to local authorities, recognising their local expertise (DCLG 2011). On the other hand, public spending has continuously been cut since the start of austerity politics of 2010’s Coalition Government (Elliot & Wintour 2010, Stewart 2016).

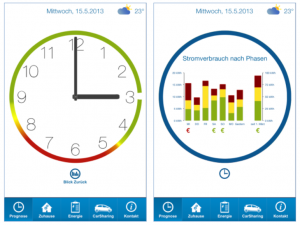

These conditions are challenging but are also an opportunity for researchers to cooperate with local governments to explore innovative ways of policy making in a constrained setting. In terms of working with citizens, in the UK planning system’s statutory forms of public consultation have been criticised for being limited and often tokenistic (Cullingworth et al. 2015). Putting planning notifications on lamp poles (Figure 2) and announcing them in the local newspaper is hardly an engaging way to include the citizens affect by planning activities.

There are therefore new opportunities to do things different and councils have been open to experiment, e.g. by using online consultation platforms such as Commonplace (Commonplace N.D.).

Going beyond that, radical approaches in planning have challenged tokenistic and symbolic inclusion as acts of neoliberal hegemony (Miraftab 2009). By routinising participation through officially sanctioned forms it depoliticises the struggle of disadvantaged and marginalised groups but do not do not entail material redistribution and social justice. Grass-roots movements all over the world have used both these ‘invited spaces’ as well as ‘invented spaces’ – spaces outside of the system, to invoke citizen rights and foster their counter-hegemonic interests. Similarly, planners and researchers should not be confined within the system (local governments, NGOs, and ‘recognised’ communities and stakeholders), but use both spaces creatively to advance a social justice agenda.

1.3 Participatory Design

In HCI, participatory approaches to designing interactive systems have a long tradition but gained momentum recently with the ‘turn to the wild’ (Carroll and Rosson 2013). Participation Design (PD) is about change in the real world, but is not a straightforward thing, as it can be configured in many ways (Vines et al. 2013). Applying to HCI as well as planning, the designer/planner is a crucial agent in shaping and configuring participation and should be reflexive in which form control is shared among participants. Who initiates participation (the designer?), who participates (the most vocal?), and who benefits? (participants, commercial actors, researchers?)

LeDantec and Fox (2015) highlight how important the work is before participation even starts. How do we gain access to a group and initiate participation? It takes time and work to establish a presence on a site, build rapport and partnerships. PD is both about choosing people to work with and being chosen by people.

A valuable example of how this can be put in practice is the PD process used by Lindsay et al. (2012) to work with people with dementia, but in my eyes applies to any PD research. They start off by building empathy for the group they work with. It is essential to have an uncritical sympathetic disposition towards them to understand their lived experiences and establish a trusted environment. A consistent point of reference from the design team helps to develop a close relationship with the participants and becomes an advocate for them in internal design meetings. A shared understanding is build through an iterative series of meetings and workshops that are thoroughly documented and analysed and then validated by the participants. Validation is important to not inadvertently disempower participants by drawing too quick conclusions. The workshop format obviously varies depending on the context, but Lindsey highlight how material design prompts help to elicit reactions.

1.4 Action Research

Foregrounding participation and shared control is central to action research and therefore relates well to HCI and Digital civics. Action research is on social action and its conditions and effects and on research leading to action (Hayes 2011). It follows a spiral of steps: planning, action, and fact-finding about the results of action. This iterative approach requires a long-term engagement of researchers in a community. It is, however, not only about researching a community, but developing an action with them to make a positive and sustainable change in a community – with them, not for them. The work is therefore highly contextualised and localised. Action research aims at an equal share between researchers and participants, which is reflected in the terminology: it does not speak of participants but of community partners.

In action research in HCI, the researcher acts as facilitator to co-design interventions and change with community partners. With technology-based interventions the question of the sustainability of action is particularly important. What happens after researchers leave the site? Taylor et al. (2013) discuss that it is important to manage different expectations around the matureness of experimental research technology and plan for a handover from the very beginning. While in an iterative development technology can continuously be improved based on community feedback, it is equally important to build capacity and skills in the community to maintain and develop technology for themselves.

2 Citizen-driven Participatory Action for Environmental Sustainability

The topics and research fields in the previous sections form the foundations of what I consider my current understanding of Digital Civics. In this section I want to look at four elements that I see as central on how to actually do Digital Civics for environmental sustainability.

As discussed earlier, the open questions around participation, in particular its hegemonic effect, make me as a Digital Civics researcher want to go beyond working with governmental institutions, non-profits, and charities through sanctioned forms of civic participation. Engaging with communities, activists, and publics, i.e. emerging groups with shared concerns, means to partner with them to explore how civic technology can support them in their aims. I will discuss these groups and the role of data and technology in the following sections.

2.1 Communities

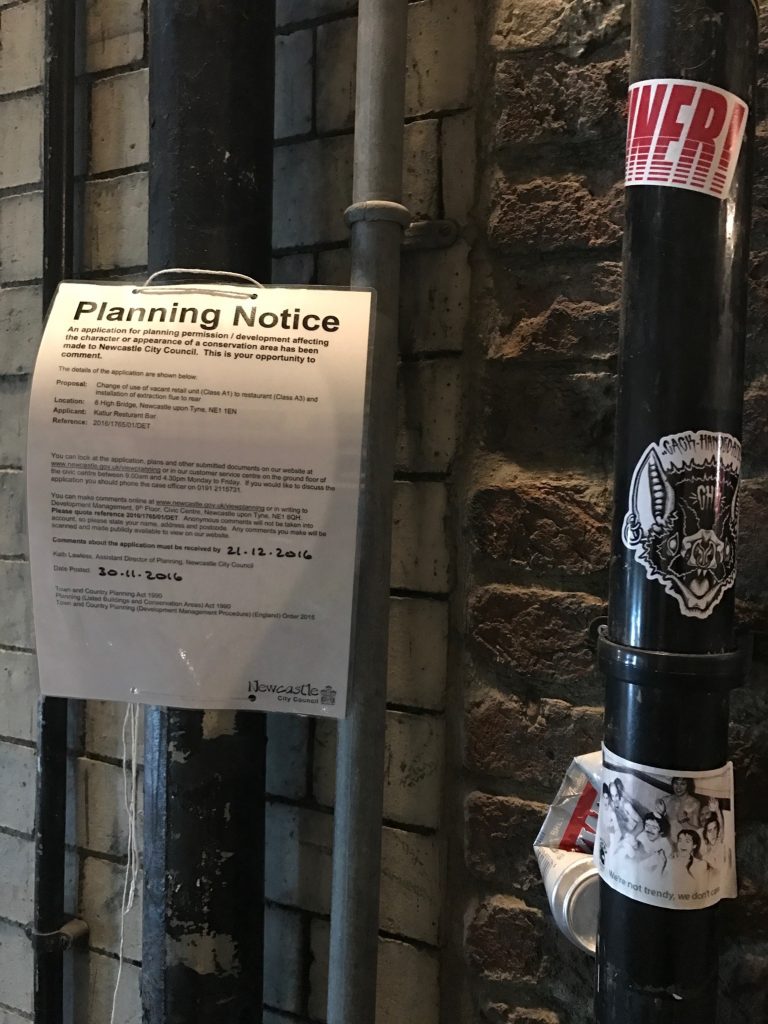

When working with a community, research has shown the tension around different understandings of how a ‘community’ is understood. Crivellaro et al.’s (2016) work on a participatory urban renewal programme showed how the housing association wanted to ‘build’ a ‘good’ community for the ‘problematic’ neighbourhood. Contrastingly, research on site revealed through a purposefully designed digital storytelling intervention in the shape of ‘travelling suitcases’ (Figure 3) the estate’s rich history through heterogeneous stories and a multitude of values, connected to specifics of the site.

This finding rejects the notion of one stable definition of community as a homogenous collective of citizens but understands community as plural, situated, partial, and contingent. Multiple voices can come together in a constructive, and not simply oppositional way. Revealing this effectively enabled residents to reflect how they essentially re-make places and collectively ‘work out’ and ‘grow’ their community. Researchers should therefore not understand community as something that is but as something that is ever becoming.

Top-down participation tried to impose a normalising view on community onto the residents, based on binaries such as ‘good’ and ‘bad’. HCI’s role is thus to facilitate dialogue among heterogeneous practices and actors and work with them instead of treating them as a space to intervene and solve a problem. So, instead of top-down, let’s go bottom-up? Let’s have a look at activists.

2.2 Activism

How can HCI and digital technologies support activists ‘on the ground’? Recently, the term ‘slacktivism’ has been coined to question the value of ICTs to mobilise masses for activists’ causes, as the value and impact of people clicking ‘like’ or sending a pre-formulated letter to political representatives remains unclear. In the end, activism is always about people showing up in person (McCafferty 2011).

However, as Asad and LeDantec (2015) have shown, the value of ICT lies at least in coordinating and facilitating already existing political work. They identified three opportunities for HCI: First, it can situate their action, e.g. by revealing issues to the public and mainstream media. Second, it helps to codify action, that is to support an effective communication and organisation of different audiences. Third, it can scaffold action by recruiting and mobilise non-group members to participate and show up in person.

How to measure impact and success of technological support for activists remains an open question. First, it is impossible to untangle it from the work they already do. Morover, their work’s impact itself is already hard to measure (Asad and LeDantec 2015).

2.3 Publics

Digital Civics can also go beyond communities and activist groups by looking at publics. Publics can be understood as dynamic formations of people around a shared issue or matter of concern. Publics are an expression of political spaces through ‘vernacular voices’ (Hauser and McClellan 2009). This notion frames politics not just as institutional discourse in a single public sphere, but extends it to everyday rhetoric that happens in many networked publics. It rejects Habermas’ model of a deliberative democracy built on consensus through rationality, favouring interested but reasonable rhetoric. Such an agonistic understanding of democracy recognizes the presence of radical difference in a pluralistic society (Mouffe 2000). Everyday discourse is thus a “‘rubbing up’ of multiple, diverging opinions” (Crivellaro et al. 2016). The purpose of technology is thus not to find solutions to problems, but to prompt new discourses and questions.

Crivellaro et al. (2016) studied the formation of a public on Facebook around a redevelopment programme of a derelict outdoor swimming pool that would have turned it into a multipurpose facility. Initially, a historised discourse around the old pool supported reminiscing and building up support against the redevelopment (Figure 4). Second, the controversial discourse shaped a collective, with its own consciousness and a political potential to become active. Third, the political was activated by moving beyond the digital by organised protest in person and attracting mainstream media. This formation and the role of ICT in it mirrors Asad and LeDantec’s research on activist groups described earlier.

Figure 4: A reminiscing, nostalgic video of the old outdoor swimming pool. One of many pieces that build up support against the redevelopment plans.

2.4 Data

Data is a key instrument in supporting change work. Often data collection itself is framed as a form of participation, as people participate by giving their data. Particularly in a smart city and big data contexts, the trend of datafication has rapidly been developing (Taylor 2015). It entails the idea that metrics can capture the ‘whole’ of human activity and social life. This abstract, decontextualised, and generalised proxy then informs decision and policy making. Some have gone so far to argue that the sheer quantity of big data allows statistical algorithms to detect patterns and react to them in real-time without needing any scientific models to explain or predict them (Anderson 2008). I disagree with this view and go with Taylor et al. (2015) who argue for the concept of data-in-place: First, data is always connected to matters of concern, therefore it is not neutral. It privileges some readings, and discounts others. Second, it loses its meaning when abstracted from place, as it shapes and is shaped by the physical world. This includes how it is captured, and where it flows. Third, there are many gaps in the data flow, it has contours shaped by people, space, place, and time. Forth, the same data can have multiple relations, logics, purposes.

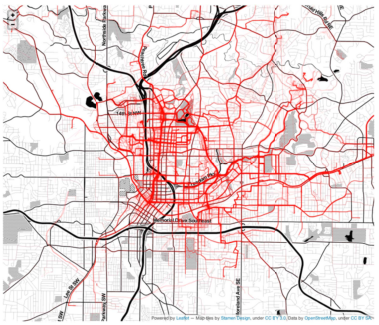

How data can have authority is illustrated in LeDantec et al.’s (2015) work on a cycling infrastructure planning project. Data’s authority here does not necessarily come from numbers, but though its representation, in this example in a planning workshop as a map representing tracked cycling trips (Figure 5). Data was used as evidence to legitimise past, present, and future actions of the planners. Data, however, was also ambivalent. It is not self evident how to interpret data or what actions should be based on it. There is always a step of collective interpretation and sense-making, which is less visible in narratives of big data approaches, as the human interpretation is hidden in the design of the algorithm.

Issues of equity and inclusion, in particular the question of who contributes data and who is excluded or does not want to contribute resemble the questions asked for participation. The cycling example, however, also showed that data has the potential to disrupt existing practices in planning as they enabled planners to work with previously unknown representations of lived experiences.

3 Conclusion: Digital Civics for Environmental Sustainability

So then, how do we do Digital Civics in the context of environmental sustainability and urban planning? Considering that I will be working with local governments and planners, as well as communities, activists, and emerging publics, I want to approach Digital Civics through participatory action research, in which the design process itself is open to be defined collaboratively. The primary aim of collaboration is therefore not to find solutions but to stimulate questions and a shared understanding of an issue. Nevertheless, I recognise that as a designer and researcher I am in a privileged position and I need to be reflexive of my personal agenda and commitments. One such commitment will most likely be around fostering environmental sustainability. When working with individuals, activists, planners, communities, organisations, cities it is therefore crucial to find ways to align these values with those of partners, who might have different priorities.

I resonate with Miraftab’s (2009) call for radical planning to stimulate historical collective memories. Their value has been demonstrated in the work of Crivellaro et al. (2014, 2016). My personal approach to doing Digital Civics research in such a setting aligns with Boehner and DiSalvo’s (2016) view on the role of HCI and design for civic technologies: First, it facilitates curiosity. HCI researchers should not seek to solve problems, but rather facilitate an understanding of the conditions around it. Second, it fosters deliberation and exchange of a plurality of voices. Third, it teaches skills and literacy to deal with data and technology, making change sustainable.

Foth’s (2015) proposal to civic technology extends the third point from using to actually making technology. By moving from digitisation to fabrication, and in a way back to the physical, hybrid approaches use physical and digital forms of accessible and engaging participation. Fostering craft and DIY culture, some speak of DIY citizenship (Ratto and Boler 2014), is a logical conclusion of a genuine partnership between researchers and citizens, were ultimately citizens don’t need researchers at all to support them in their goals. In that sense technology as well researchers become enablers for change instead of imposing solutions.

4 References

Anderson, Chris. 2008. The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete. Wired.com. Retrieved December 13, 2016 from http://archive.wired.com/science/discoveries/magazine/16-07/pb_theory/

Asad, M. and Le Dantec, C. a. 2015. Illegitimate civic participation: supporting community activists on the ground. Proc. CSCW ’15 (2015).

Boehner, K. and DiSalvo, C. 2016. Data, Design and Civics: An Exploratory Study of Civic Tech. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (2016), 2970–2981.

Brynjarsdottir, H. and Håkansson, M. 2012. Sustainably unpersuaded: How persuasion narrows our vision of sustainability. Proc. CHI ’12. (2012), 947–956.

Carroll, J.M. and Rosson, M.B. 2013. Wild at Home. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction. 20, 3 (Jul. 2013), 1–28.

Commonplace N.D. Commonplace – Online Community Consultation Platform. Retrieved December 13, 2016 from http://www.commonplace.is/

Crivellaro, C. et al. 2014. A Pool of Dreams: Facebook, Politics and the Emergence of a Social Movement. Proceedings of the 32nd annual ACM conference on Human factors in computing systems – CHI ’14 (2014), 3573–3582.

Crivellaro, C. et al. 2016. Re-Making Places: HCI, “Community Building” and Change. (2016).

Cullingworth, B. et al. 2015. Town and Country Planning in the UK. Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon, UK.

DCLG (Department for Communities and Local Government) 2011. A plain English guide to the Localism Bill.

DiSalvo, C. 2010. Design, Democracy and Agonistic Pluralism. Proceedings of the Design Research Society Conference 2010. (2010), 366–371.

Dourish, P. 2010. HCI and environmental sustainability: the politics of design and the design of politics. Proc. DIS ’10 (2010), 1–10.

Dourish, P. and Mainwaring, S.D. 2012. Ubicomp’s Colonial Impulse. UbiComp ’12 (2012), 133–142.

Elliot, L. and Wintour, P. 2010. Budget 2010: Pain now, more pain later in austerity plan. The Guardian. Retrieved December 12, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/jun/22/budget-2010-vat-austerity-plan

Fogg, B.J. 2002. Motivating, influencing, and persuading users. (Jan. 2002), 358–370.

Foth, M. et al. 2015. From Users to Citizens: Some Thoughts on Designing for Polity and Civics. ozCHI ’15 (2015), 623–633.

Hauser, G.A. and McClellan, E.D. 2009. Vernacular Rhetoric and Social Movements: Performances of Resistance in the Rhetoric of the Everyday. Active voices: Composing a Rhetoric for Social. S. McKenzie Stevens and P. Malesh, eds. State University of New York Press.

Hayes, G.R. 2011. The relationship of action research to human-computer interaction. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction. 18, 3 (2011), 1–20.

Le Dantec, C.A. and Fox, S. 2015. Strangers at the Gate. Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing – CSCW ’15 (New York, New York, USA, Feb. 2015), 1348–1358.

Le Dantec, C.A. et al. 2015. Planning with Crowdsourced Data: Rhetoric and Representation in Transportation Planning. Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing – CSCW ’15 (2015), 1717–1727.

Lindsay, S. et al. 2012. Empathy, participatory design and people with dementia. Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’12 (New York, New York, USA, 2012), 521.

McCafferty, D. 2011. Activism vs. slacktivism. Commun. ACM. 54, 12 (2011), 17–19.

Miraftab, F. 2009. Insurgent Planning: Situating Radical Planning in the Global South. Planning Theory. 8, 1 (2009), 32–50.

Mouffe, C. 2000. Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism? Political Science Series. 72 (2000), 17.

Morozov, E. 2013. To Save Everything, Click Here: Technology, Solutionism, and the Urge to Fix Problems That Don’t Exist. Allen Lane.

Prost, S. et al. 2014. “Sometimes it’s the Weather’s Fault” – Sustainable HCI & Political Activism. CHI EA ’14 (2014).

Prost, S. et al. 2015. From Awareness to Empowerment: Using Design Fiction to Explore Paths towards a Sustainable Energy Future. CSCW ’15 (2015).

Ratto, M. and Boler, M. 2014. DIY citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media. MIT press.

Stewart, H. 2016. Fresh austerity measures signalled in Osborne’s eighth budget. The Guardian. Retrieved December 12, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/mar/16/chancellor-fresh-austerity-measure-in-budget

Taylor, A.S. et al. 2015. Data-in-Place: Thinking through the Relations Between Data and Community. Proc. CHI 2015 (2015).

Taylor, N. et al. 2013. Leaving the wild. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’13 (New York, New York, USA, Apr. 2013), 1549.

Vines, J. et al. 2013. Configuring participation: On how We Involve People in Design. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’13 (New York, New York, USA, Apr. 2013), 429.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply