The Faces Behind the Interface: Putting the Human back into Human Computation through Turkopticon

This week’s paper “Turkopticon: interrupting Worker Invisibility in Amazon Mechanical Turk” by Irani and Silberman (2013) takes on the retail giants Amazon, specifically the Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) and explains the development of an activist technology that aims to put some power back into the hands of the system’s digital workers.

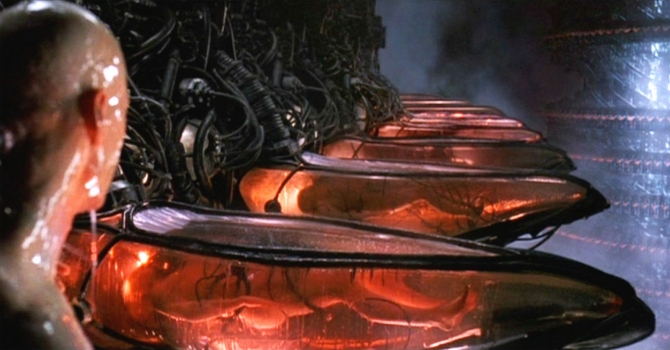

The paper begins by introducing the AMT as an online infrastructure that allows requesters (or “employers”) to digitally crowd source the completion of “microtasks” by a globally-reaching human workforce, usually in exchange for money. Such human computation has been heralded as the “new frontier” for HCI research and innovation. However, as Irani and Silberman point out, the rhetorical focus on the innovation behind the technology has shifted attention away from the faces behind the interface. This erasure of the human element is a powerful means of suppressing broader considerations of the ethics behind labour market crowdsourcing and strips AMT’s “employees” of the worker rights afforded to those from other, non-digital working environments; in essence, AMT makes its workers invisible.

The paper then goes on to highlight how such invisibility affords AMT’s employers a worrying amount of power. As Amazon legally defines the AMT workers as contractors, workers are exempt from the minimum wage requirements of their respective countries. Not only can employers therefore set whatever price they desire for the service they request, but so too can they choose to reject work after-the-fact without any obligation to pay for the service, or even provide a justification for the rejection. Even where an employer decides to reject a job without payment, the AMT participation agreement requires that all workers give up their intellectual property rights to anything they produce, therefore allowing employers to use submissions without paying at all.

Despite openly allowing for wage theft by employers, AMT’s system ensures that workers are not even able to voice their dissatisfaction in such an event; employers have no obligation to respond to inquiries or be held accountable for their actions, workers have no means of rating employers and the sheer volume of the AMT workforce means that a loss of individual workers has zero impact in a labour-surplus market. Whilst the AMT is a system I had not personally come across before reading this paper, I must admit, given Amazon’s reputation for labour conditions more generally, I find myself unsurprised by their lack of consideration for worker’s rights in the digital context. If Amazon don’t care about their workers on the ground, do we really expect them to care for them in the cloud?

In response to such ethical concerns, Irani and Silberman developed Turkopticon, a browser extension that aims to put some of the power back into the hands of AMT’s workers. This system flips the table and upsets the power imbalance that pervades in the existing employer-oriented system by allowing workers to publically review employers. Reviews are based on four criteria: communicativity (responsiveness), generosity, fairness and promptness (of payment and response), as well as allowing for open-ended comments.

In creating this infrastructure for mutual aid, the authors have increased the visibility and voice of workers, made AMT a more transparent marketplace, increased pressure on employers to behave in a more ethical way and opened up wider questions and debate around the ethics involved in the crowdsourcing of labour. Sadly however, despite having shown promise and positive impact, the intention to evoke real changes from Amazon to the underlying flaws in the system itself has not come to fruition. The future of Turkopticon now hangs in the balance and its maintenance and continuation is supported solely by academic research grants. Whilst the intention was to change AMT at its core, when this seems unlikely we must now consider how sustainable the Turkopticon can be moving forward and what that might mean for workers’ rights in the future.

The paper I have chosen this week, “Web Workers Unite! Addressing Challenges of Online Laborers” by Bederson and Quinn (2011) further discusses the ethical issues of crowd-sourced human computation and explores similar issues around online worker’s rights from a broader perspective.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply