Whose participation is it anyway? Exploring publics, HCI and the Digital Civics agenda

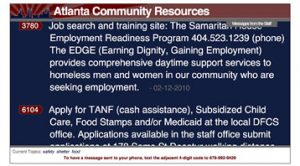

Chris Le Dantec’s paper [1] details the design and deployment of a bespoke information system, the Community Resource Messenger (CRM), with a shelter in Atlanta that offers social support to homeless families.

Aligning with the Deweyan notion of publics [2] – which notes the existence of multiple publics created through shared social conditions and the common identification of issues – he argues that HCI and systems design provides space for both engagement and action with and by multiple publics. In this conception, technology – and the participatory design of it – is about more than just ‘creating products’ [3]. It has a role in facilitating the construction, ongoing and future work of these publics. Le Dantec argues that this places emphasis on structuring sustained participation throughout an artefact’s lifecycle; indeed, a key criticism of PD is the fleeting nature of this participation [4].

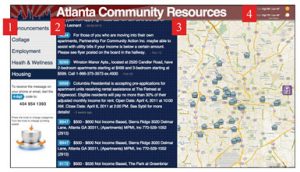

Le Dantec states that this theoretical approach informed the design and execution of the CRM project. Two versions were deployed, with the latter building upon feedback identified during the former. What was particularly interesting to me was the way in which the system was perceived following the redesign – in looking more “professional” and less “ambiguous” than the first deployment, the ‘Shared Message Board’ became nothing more than an ordinary message board where staff disseminated information to residents. I agree with Le Dantec’s analysis that this probably arose as a result of how the information was read, and the perception of legitimacy that is needed for participation. It was precisely the ambiguity and “unprofessional” design of the first system that made participants feel comfortable in engaging with it.

The deployments showed the importance of thinking carefully about design and about users. The researchers’ interpretation of feedback that the second deployment should be more information-driven is probably to blame. There is always the risk that these things can happen when researchers gather feedback, then “go away” to interpret this and work up a new design, instead of both interpreting feedback and designing the system with participants.

The first (left) and second (right) deployment of the Community Resource Messenger (CRM) system

It is also important to recognise the context within which you are working – after all, the shelter’s purpose is one embedded in a transactional mode of service delivery that transcends health, education and social services. It is this mode that the Digital Civics agenda is seeking to disrupt – but where does this leave PD? After all, the system was designed to a specification that staff and residents (were thought to have) wanted. So is it right to push our agenda if this isn’t what participants want? And what else does the existence of a multiplicity of publics and stakeholders mean in practice? I will look to explore these questions further through my research.

I really enjoyed this week’s session on experience – in fact it was one of the most interesting sessions yet. Our group was set the task of arguing for or against designing emotion in user experience (UX). Whilst this is obviously a difficult question, I managed to relate the concept to my previous understanding of UX and contribute towards formulating an argument in our group for emotion contributing to a richer UX that engages the user in a human way and sustains interest and curiosity in the end use.

[1] Le Dantec, C. A. Participation and Publics: Supporting Community Engagement. In CHI ’12: Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp1351–1360, New York, NY, USA, 2012. ACM.

[2] Dewey, J. The Public and Its Problems. Swallow Press, Athens, OH, (1954 [1927]).

[3] Shapiro, D. Participatory design: The will to succeed. In Proc. CC 2005, ACM (2005), pp29–38.

[4] Light, A. and Akama, Y. Structuring Future Social Relations: The Politics of Care in Participatory Practice. In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference: Research Papers – Volume 1 (PDC ’14), October 2014: pp151-160.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply