Critical Design: Materialised Critical Theory and Ideological RtD

Critical Design: Materialised Critical Theory and Ideological RtD

This week’s topic of the HCI course is “Designing as Researching” and I picked to discuss Jeffrey and Shaowen Bardzell’s paper titled “What is ‘Critical’ about Critical Design?” [1]. I chose this over the others because I have read a few other publications by the same authors and I like how they relate HCI issues to theories and conceptual frameworks from other disciplines such as philosophy, literary studies, arts and history. The Bardzells are known to be eloquent critical thinkers who often shed a different light on contemporary design practices in order to reflect on their value for the field’s transformative claims (which is a specifically important topic for Digital Civics being all about implementing empowering technologies).

I think critically therefore I can be better

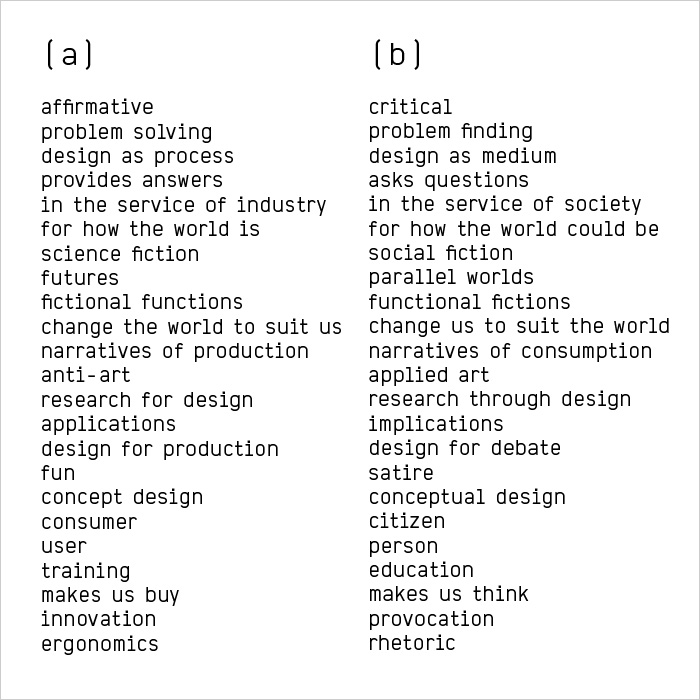

In the paper at hand the authors discuss Critical Design and its limited adoption in HCI (which they find surprising considering that both share many ethical values and deal with sociocultural implications of design). They refer to Dunne and Raby’s original concept of Critical Design and describe how their work draws on the Frankfurt School of critical theory (Horkheimer, Adorno, Marcuso). The basic critique is here that dominant systems use mechanisms of reification to maintain the status quo and make it seem to be the natural/good way of things. Capitalism for example uses consumer culture and mass media to reify its ideology. This comes at cost of everything and everyone outside of the dominant system (eg. people without money, things without financial value, ethical values without a prize). The goal of critical theory is therefore to uncover reifying mechanisms, create collective consciousness and bring about social emancipation. Critical Design, now, sees design as one potential means of reification but also of disruption. Dunne and Raby therefore distinguish between affirmative and critical design.

However, while this is a constructive train of thought for design in general, the Bardzells criticize that the concept is hard to implement and that there are small contradictions in the work of Dunne and Raby (eg. the proclaimed differences between art and critical design). In order to make Critical Design more accessible for HCI research, they identified two genres of critical thought within the literature of the past 150 years, which offer pragmatic benefits how critical concepts can be applied: Critical theory (as a sociocultural scepticism) and metacriticism (as a medium-/discipline-specific way of analysis).

By synoptically outlining the respective complementing features they also highlight shared qualities:

- Critical activity seeks to create perspective-shifting holistic understandings.

- Theory is of challenging speculative nature and makes no claim to be right.

- Critical engagement means to apply a dialogic methodology.

- The aim of critical practice is the improvement of the public’s cultural competence.

- Reflexivity is key to critical thought: It admits that its own rationality is limited and not objective.

Eventually, the authors come up with following criterion for design to meet in order to be qualified critical:

“a design research project may be judged ‘critical’ to the extents that it proposes a perspective-changing holistic account of a given phenomenon, and that this account is grounded in speculative theory, reflects a dialogical methodology, improves the public’s cultural competence, and is reflexively aware of itself as an actor—with both power and constraints—within the social world it is seeking to change.” [1:3304]

Critical Design as a form of Research through Design

While it was interesting to think about the implications of design being critical and the role of implementing subversiveness into objects (as seeds for changing the world in the long run through a shift in public awareness), it was also a constructive thought experiment to figure out how Critical Design exactly fits into Research through Design (RtD). The Bardzell’s don’t really depict their view and simply state that “[c]ritical design is a research through design methodology that foregrounds the ethics of design practice, reveals potentially hidden agendas and values, and explores alternative design values” [1:3297].

Having read a couple of other accounts on RtD [2–5] I had understood it so far as a still evolving pragmatic conception using design as a way to create new situated knowledge. In 2007 Zimmerman, Forlizzi and Evenson proposed RtD as a formalised model which “allows interaction designers to make research contributions based on their strength in addressing under-constrained problems” [5:493]. This quote indicates the scientific challenge for RtD: The problem that design does not really fit into traditional research frameworks and a-priori hypothetical thinking. Design cannot provide a theory, which is falsifiable in the Popperian sense, since it just constitutes one possible solution for a defined problem. However, it does offer something else: A basis for critical discussion and reflection and a possibility of finding a good design which has an impact on a given problem.

Storni highlighted three key values for successful RtD: “RtD is rigorous when it is modest, accountable, and generative.” [4:76] In a sense these values overlap with the pragmatic characteristics of Critical Design outlined by the Bardzells:

Modesty goes along with the openly speculative nature not claiming to be right. As Gaver also stated “research through design is likely to produce theories that are provisional, contingent, and aspirational” [3:937]. Accountability is a matter then of reflexivity and the transformative aim. Rather than making statements about what is true, design has a provocative fictional appeal and focusses on what could be and proactively questions what might be the “right thing” [5]. Practically, this requires the designer/researcher to be a critical thinker and thorough documenter by pointing out the important features of the design as being one possible ultimate particular. Trying out different possibilities implies that design, and therefore also RtD, is generative. It does not only constantly create new artefacts but it also produces new knowledge through its empirical effects [4]. Critical Design however goes a step further and hopes for an additional implication: the ultimate improvement of the public’s cultural competence and along with it socio-cultural change. In this way, critical design can be understood as an ideological version of an otherwise rather pragmatic RtD.

References

- Jeffrey Bardzell and Shaowen Bardzell. 2013. What is “critical” about critical design? Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’13: 3297. http://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2466451

- Ditte Amund Basballe and Kim Halskov. 2012. Dynamics of Research through Design. Proceedings of DIS2012, 58–67. http://doi.org/10.1145/2317956.2317967

- William Gaver. 2012. What should we expect from research through design? Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 937–946. http://doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2208538

- Cristiano Storni. 2015. A Personal Perspective on Research Through Design. interactions 22, 4: 74–76. http://doi.org/10.1145/2786974

- John Zimmerman, Jodi Forlizzi, and Shelley Evenson. 2007. Research through design as a method for interaction design research in HCI. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems – CHI ’07, ACM Press, 493. http://doi.org/10.1145/1240624.1240704

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.