Town Planning & HCI: Challenges of Participation

Engaging citizens in decision-making has been a widely debated topic for a number of years in town planning. Over recent years, it has received a lot of attention as the political rhetoric of national and local government is to devolve power to local people. However, it is not just the planning sector that has seen this change and it is becoming an important consideration in almost all fields of thinking.

With multiple sectors attempting to conquer the challenge of engaging citizens, my focus in this blog is to draw attention to the challenges of participation faced by town planning and HCI. First, I will briefly outline my research interests and provide an outline of the contextual issues affecting my research. Second, I will briefly introduce how HCI can be a welcome addition to the methods used for participation in town planning. I will then focus on three key issues of participation in both fields drawing on the relevant areas of HCI which can inform future research and practice. Finally, in summary, I will consider what the future holds for participation.

My research interests

Simply put, my main interest is to improve participation in town planning. The digital civics agenda aims to create new means of communication between citizens and local government to allow local people to shape their own futures [19]. In the current planning system in the UK, our towns and cities are planned by local government planning departments with minimum requirements for engaging the public. At a citywide level, planning officers consult on draft policy documents using traditional methods such as public meetings and forums but technology is heavily under-utilised in this process [2].

At a local level, neighbourhood planning was introduced by the Localism Act in 2011 which challenged the traditional ways of ‘doing’ planning and provided communities with real power to take control of decisions. Although this challenged the power dynamics by devolving power to local people, the methods of engagement have still focused on traditional approaches and have under-utilised technology.

Although both scales of planning need to improve their participation processes, supporting neighbourhood planning through HCI provides an opportunity to spark grassroots community action and it is here that I will focus my attention.

Town planning contextual issues

Despite their being a drive to engage citizens in planning over the years, the ways of doing so have, on the whole, remained partially successful. Neighbourhood planning was one of the most radical changes to planning law in recent history but it has failed to take hold as people would have hoped. A utopian view of empowered citizens, improved communication between local people and government and strong, irrepressible communities has not been achieved thus far [20].

In spite of the addition of neighbourhood planning to the town planning sector, those attracted to producing a plan has mainly come from those already engaged in the planning system – mainly those from more resource-rich areas [23]. The process of producing a neighbourhood plan is long and complicated and requires some level of planning expertise making it inaccessible to many.

The need to bring planning into the 21st century is clear as the under-utilisation of technology seems to be entrenched into the system – even for neighbourhood plans. During my research for my Masters dissertation, local planning officers reported that they were scared and sceptical of technology to support participation despite their knowledge that it is a popular mode of communication for a large section of the population.

How can HCI help?

Within the realms of HCI there are a whole host of technologies and methods that could be hugely beneficial to support the neighbourhood planning process. This could be to support existing interested neighbourhood planning groups and to support bringing forward groups from more resource-deprived areas. Technology can be used to “inspire and facilitate” citizen participation in planning, encouraging local people to take control of the decisions in their neighbourhood [10]. Below are three examples (of many) that could support this process.

Participatory Design

Participatory design practices have the potential to support neighbourhood planning processes. Ultimately, neighbourhood planning is a participatory process but using technology in this realm is an under-explored area. In addition, it would be possible for neighbourhood planning groups to design technology to specifically suit their needs during the process.

In my blog post from week 2, I discuss the opportunities and challenges presented by participatory design as set out by Light and Akama. It is often said that participatory processes achieve longer-term benefits for those involved but often these are assumed [18]. We believe that such participatory processes have the ability to build capacity, strengthen community ties, improve relationships and spark new discussions and debates [18]. To ensure this, Light and Akama suggest creating the notion of ‘care’ amongst participants which can foster care in the group which can extend into the wider community.

As well as the notion of care in participatory design, DiSalvo et al. [11] also state that the participatory process itself is “not enough”. They suggest considering how the participatory process can also be a form of politics or political action. This was the intention through the Neighbourhood Networks project to “increase the visibility and volume of their [participants] voices and capture the imagination and attention of others in support of their agendas”.

During my experience of facilitating Fish Quay Neighbourhood Plan, both of these issues inadvertently came about. With a multitude of local residents with different agendas it was clear that participants did foster ‘care’ amongst themselves and the wider community. In addition, the neighbourhood planning group and off-shoots of the group used the process as political action to begin the process of a community-led and community-run heritage centre in their area.

It is clear that not only could neighbourhood planning benefit from HCI but HCI could benefit from neighbourhood planning as a way to explore both the notion of care and the use of participatory processes for political action.

Online communities

I discussed online communities in my blog post in week 4 with my focus on people’s motivations for using Facebook. Upon reflecting on the discussions with others and reading other papers, online communities can be an excellent resource to engage local people in town planning. With Facebook having over 1.5 billion users and Twitter averaging 307 million users each month [21], using social media and other online platforms to engage local people could be hugely beneficial to reach a new section of the population that would otherwise not engage in the planning process.

Opinion is divided about the use of online communities in planning with some suggesting it allows messages to reach more people, the systems are accessible, they are cost-effective, people can express themselves freely, and the information can be processed quicker [2]. However, others have argued that it online communities can exclude those who are not able to access them, the diversity of participants would be limited and that it could provide a new platform for those already engaged rather than engaging new people [23]. Although the debate continues, online communication through social media is not part of our everyday lives and is an important component when communicating with the public [14].

There are examples both in research and practice where online communities have been successfully used to develop neighbourhood plans and to communicate with large sections of the population [6]. Great Aycliffe Neighbourhood Plan in County Durham have successfully communicated via Facebook to almost 1000 people and the audience was ever-growing. Through Facebook they were able to engage with a section of the population they had not reached previously through face-to-face methods and they increased the diversity of participants enormously. In addition, they had two-way communication with the local community with idea generation, comments and feedback that were helpful and included as part of the neighbourhood planning process.

The use of online communities can be beneficial in the planning process in general, and in neighbourhood planning particularly. The key to success for wider populations is to use a mixture of methods and to ensure a ‘one size fits all’ approach is not taken.

Tangible computing

Tangible computing could have so many benefits when used in a planning context as already shown by a range of research. Personally, this was an area of HCI that I knew very little about and grappled with the concepts of in my blog post in week 5, however, I can see the great value to the town planning field. Tangible computing uses physical objects to interact with the digital. It gives “physical form to digital information” [24] by using physical objects to represent and control that information.

For planners, a great difficulty can be to communicate the plans they have produced for a town to the public [17]. With the public increasingly being involved with planning at a citywide level and, in particular, at a local level with neighbourhood planning, it is essential to be have tools that can communicate complicated planning information [4]. Tangibles offer the opportunity to display information in a way that non-professionals could easily understand using a range of data from digital data to drawings [4]. In addition, the Smart Citizen Dashboard shows how using physical buildings as a projects screen with a tangible interface to collect participant’s feelings and views about their city can be an interactive way to engage the public [3].

Despite the many advantages and benefits to town planning through the use of tangible computing, the systems can be complicated to design, set up and use. That’s not to suggest they shouldn’t be used but to say that we need to create simple systems that are user-friendly. This could allow neighbourhood planning groups to use them during the planning process and to engage the wider public in their plan.

Key issues of participation in planning and HCI

Although there is clearly potential for HCI methods and technologies to help with participation in neighbourhood planning, challenges are still faced. Between planning and HCI, engaging citizens can be a difficult task with a range of factors at play which must be considered to ensure participation is a positive experience and does not do more harm than good [20].

I will focus on three key issues that are faced in both planning and HCI in participation processes:

- Control and voice

- Participants achieving their potential

- The changing role of the researcher

Control and Voice

In any participation process in any field of thinking, the issue of control and voice will arise. In town planning the issue centres on where the power lies and, therefore, are the planners in control of the process or are the public? In addition, there will always be multiple opinions and voices in a planning process from members of the public and who should we listen to? Likewise, in the field of HCI, should the researcher be in control of a process or should it be participants and users?

The culture of participation has shifted power away from planners and researchers towards participants by supporting them to take control in shaping the systems, places or services they use [13]. In both planning and HCI, there is a view that allowing people to participate in shaping the outcomes of designs that will affect them is not only good practice but a moral obligation [8, 9].

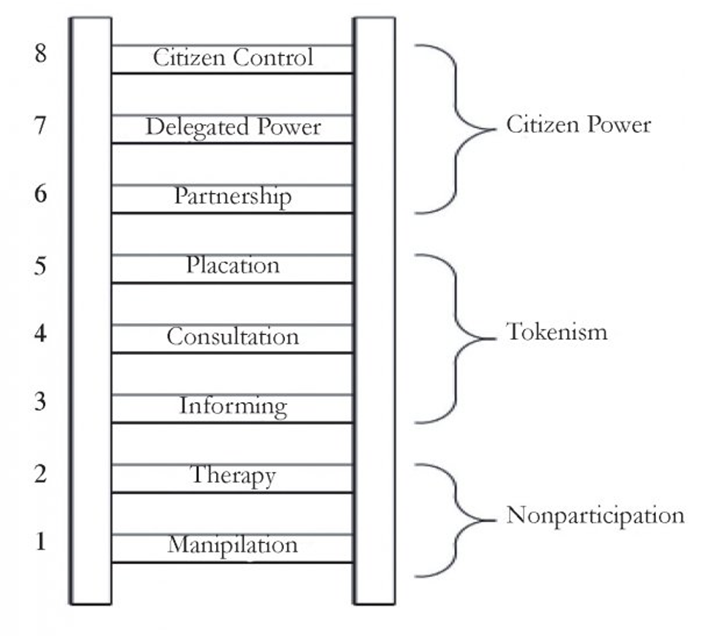

Although it is important to involve people in decisions, the amount of power given to the public can be a difficult decision. Arnstein was one of the first to propose the idea that the “extent of citizens’ power in determining the end product” [1] could be valuable (see image below). Since then, others have claimed the model to be too simplistic and proposed new models [7, 22], however, the central idea remained: the extent of power given to participants could determine the end product. Not enough power could be seen as a tokenistic process yet too much power could result in designs or decisions that are not appropriate. With people made into co-designers and co-creators, a whole host of other issues can emerge including whether people have the necessary skill set and the time-consuming nature of such projects, to name but a few.

In addition, any design process in HCI or neighbourhood planning process includes multiple stakeholders which each hold different views and opinions. Reconciling all of the viewpoints to come to a final decision can be difficult and raises the question of who’s voice should we listen to? There can be concerns that participants are often disenfranchised by the alternatives [25] which could present both an opportunity and a risk to the process.

It is also clear that throughout any process, planners or researchers are not able to engage with every member of society who could be affected by the product or decisions. In such situations, it must be recognised that as well as multiple opinions within the process, there will be many needs from the public that are not part of the process which must be considered by those making decisions [10].

Ultimately, devolving power to participants can be a rewarding experience which produces more bespoke results to suit people. It should also be remembered that quite often we presume that people want to be in control and make decisions but this is not always the case.

Participants achieving their potential

One of the key practical issues in participation, especially when devolving power to stakeholders, is the question of the skillset needed for the project at hand. Many researchers and practitioners are of the opinion that experts are needed to carry out projects to their full potential. However, this should not be the case with participants able to contribute enormously to decision-making processes.

Instead, the focus should be on the practitioner or researcher knowing how to elicit the knowledge and opinions from users [25]. In fields where technical knowledge is required, such as HCI and town planning, it should not be expected that participants are left on their own with no support. The researcher still has skills and experience to contribute to a process and this should be captured.

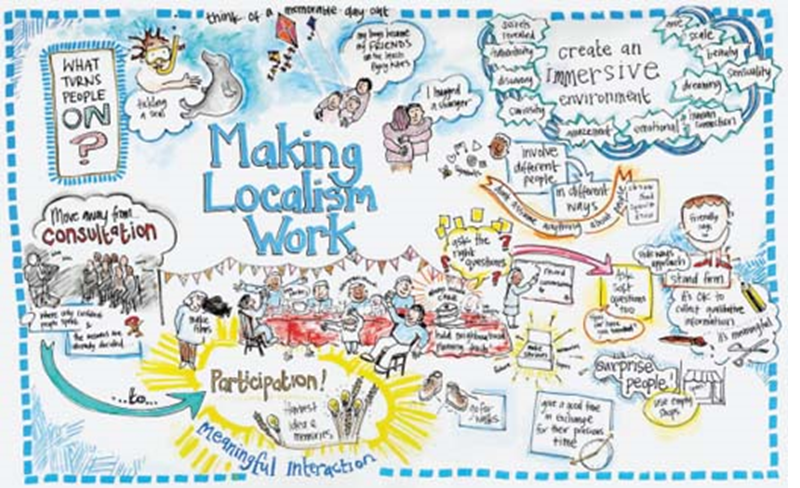

In addition, the methods used during participatory projects are key to eliciting knowledge from users. Methods such as interactive workshops, games, participatory events and other innovative techniques can be used in projects to support people in giving their views [10]. Participants have highly valuable contributions to HCI designs and neighbourhood planning processes alike, but it is how these views are collected and how the project is shaped that ensures their potential is achieved.

To successfully support participants during projects, developing new techniques and technologies can be beneficial, as mentioned during the earlier sections of this blog. Also, as Hagen and Robertson [15] argue, researchers and planners alike should not suggest a diminished or increased role for participants in projects, but should consider the context of each situation and, as a group, collectively decide what is appropriate.

The changing role of the researcher

The final challenge I have focused on is the changing role of the researcher, something which has been hinted at through the other two key challenges. Not only is this the case for HCI researchers, but also for planning practitioners. Championing participation and carrying out participatory processes, whether in research or practice, means becoming an experienced facilitator [16].

The role of the researcher is moving towards someone who configures participation, creates transparent processes, informs participants of the opportunity to get involved and guides participants through the process [25, 10]. In the past when participation wasn’t so widely heralded, it was quite often said that decisions make about participation could work against meaningfully involving the community [8] and that most participation was tokenistic. Now this is no longer acceptable and practitioners and researchers must consider their role in participatory processes.

By devolving power and control to participants, the researcher or planner removes themselves from the process and they become a facilitator, mediator and advisor. The degree to which power is given to participants does determine how removed they become. In participatory processes, even when deciding whose voice should be considered and listened to, the decisions should be taken by the participants themselves rather than the researcher. In addition, the researcher or planner must become experts in eliciting information from others and facilitating participants’ knowledge.

Changing cultures as the ultimate goal?

By using HCI technologies in the planning process and by considering the issues faced by the both fields in participation, what is our ultimate goal? Obviously improving participation in decision-making is key but what about broader cultural changes in society and politics. Wouldn’t it be great if, by doing participation well, we could change organisational cultures to make technology and participation more acceptable and sought after?

In some cases in both HCI and town planning, projects that could have been successful have sometimes failed because of the culture and politics of the organisations involved [15]. Even grassroots community action can often struggle to make the intended impact even when they have support in principle from organisations and only once results are achieved are projects and processes taken seriously [5].

Currently organisational cultures in local government stick with traditional participation methods and are finding it difficult to let go of their current practice but it is possible to change this [23, 12]. If we can develop participation practices, it should be about more than the actual product being produced (whether a technology design or a neighbourhood plan) and recognise the potential for participation to change cultures and roles [10].

Although overcoming barriers to participation can be a difficult task, examples such as those mentioned in the HCI section are proof that it can be done successfully. If we do not consider these challenges and work to overcome them, opportunities are lost [25]. We can produce more innovative and inspiring work by aspiring to overcome challenges and aiming to provide new opportunities for citizens to participate in civic life.

Future research must continue to consider participation in HCI and in town planning both separately and together. Work could centre on improving participation, involving marginalised groups and expanding HCI technologies into the planning field more explicitly.

- Arnstein, S. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation in the USA. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35:4, 216-224.

- Baker, M., Coaffee, J., & Sherriff, G. 2007. Achieving successful participation in the new UK spatial planning system, Planning Practice and Research, 22:1, 79-93.

- Behrens, M., Valkanova, N., & Brumby, D. P. 2014. Smart Citizen Sentiment Dashboard: A Case Study Into Media Architectural Interfaces. In Proceedings of The International Symposium on Pervasive Displays,

- Ben-Joseph, E., Ishii, H., Underkoffler, J., Piper, B., & Yeung, L. 2001. Urban simulation and the luminous planning table bridging the gap between the digital and the tangible.Journal of Planning Education and Research, 21:2, 196-203.

- Botero, A., & Saad-Sulonen, J. 2008. Co-designing for new city-citizen interaction possibilities: weaving prototypes and interventions in the design and development of Urban Mediator. PDC 2008, 266-269.

- Brereton, M., Roe, P., Foth, M., Bunker, J. M., & Buys, L. 2009. Designing participation in agile ridesharing with mobile social software. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual Conference of the Australian Computer-Human Interaction Special Interest Group: Design: Open 24/7,257-260.

- Brownhill, S. & Carpenter, J. 2007. Increasing participation in planning: emergent experiences of the reformed planning system in England, Planning Practice and Research, 22:4, 619-634.

- Burby, R. 2003. Making plans that matter: citizen involvement and government action, Journal of the American Planning Association, 69:1, 17-33.

- Caroll, J., & Rosson, M. 2007. Participatory design in community informatics, Design Studies, 28:3, 243-261.

- Dalsgaard, P. 2010. Challenges of participation in large-scale public projects. InProceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, 21-30.

- DiSalvo, C., Nourbakhsh, I., Holstius, D., Akin, A., & Louw, M. 2008. The Neighborhood Networks project: a case study of critical engagement and creative expression through participatory design. In Proceedings of the Tenth Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design 2008,41-50.

- Ehn, P. 2008. Participation in Design Things. PDC 2008, 92-101.

- Engeström, Y., Sannino, A., Fischer, G., Mørch, A. I., & Bertelsen, O. W. 2010. Grand challenges for future HCI research: cultures of participation, interfaces supporting learning, and expansive learning. In Proceedings of the 6th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Extending Boundaries, 863-866.

- Evans-Cowley, J. & Hollander, J. 2010. The new generation of public participation: internet based participation tools, Planning Practice and Research, 25:3, 397-408.

- Hagen, P., & Robertson, T. 2010. Social technologies: challenges and opportunities for participation. InProceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, 31-40.

- Irvin, R., & Stansbury, J. 2004. Citizen participation in decision Making: is it worth the effort?, Public Administration Review, 64:1, 55-65.

- Ishii, H., Ben-Joseph, E., Underkoffler, J., Yeung, L., Chak, D., Kanji, Z., & Piper, B. 2002. Augmented urban planning workbench: Overlaying drawings, physical models and digital simulation. InProceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality,

- Light, A., & Akama, Y. 2014. Structuring future social relations: the politics of care in participatory practice. In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference: Research Papers-Volume 1, 151-160.

- Olivier, P., & Wright, P. 2015. Digital civics: taking a local turn. Interactions, 22:4, 61-63.

- Shneiderman, B. 2011. Technology-mediated social participation: the next 25 years of HCI challenges. InHuman-Computer Interaction. Design and Development Approaches, 3-14.

- Twitter: number of monthly active users 2015 | Statistic: 2016. http://www.statista.com/statistics/282087/number-of-monthly-active-twitter-users/. Accessed: 2016- 01- 11.

- Tritter, J.Q. & McCallum, A. 2006. The snakes and ladders of user involvement: moving beyond Arnstein, Health Policy, 76:2, 156-168.

- Twitchen, C., & Adams, D. 2011. Increasing levels of public participation in planning using web 2.0 technology. Centre for Environment and Society Research working paper series, 5, 1-10.

- Ullmer, B., & Ishii, H. 2000. Emerging frameworks for tangible user interfaces. IBM systems journal 39, 3:4, 915-931.

- Vines, J., Clarke, R., Wright, P., McCarthy, J., & Olivier, P. 2013. Configuring participation: on how we involve people in design. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 429-438.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.