Empowering Users in a Fragmented World of Opinionated Technology

Introduction

The smartphone revolution promised us that whatever you want to do, “there’s an app for that”[39]. We do carry a vastly powerful portfolio of possibilities in our pockets, but usage is complex. The way we can perform tasks is constrained and limited. Our data is locked into different formats and apps. We can only use technology in the ways that we are allowed. Computers should be general purpose tools you can use to achieve your goals, but in reality computer use means participating in constrained, walled-garden user experiences.

The most critical Digital Civics issue as we go forward in the post-Web 2.0, Internet-everywhere era is this: how do we create technology that truly empowers people in their daily lives, when today’s digital reality is a complex, fractured web of software and services shaped by companies motivated to disempower us?

I will make the case that empowerment is a central issue for HCI practitioners and designers (as it always has been) (Section 1), that current trends are removing user freedom (Section 2), and frame empowerment as a grand challenge for the emerging fourth wave of HCI (Section 3).

Section 1: Empowering Users -The Story So Far

Defining Empowerment in an HCI context

In the “human factors” era people were considered as “operators” of machines. Humans were secondary actors, having no goals other than to operate the machine. The early HCI field of the 1990s (the “first wave”) recognised human actors[2] operating in workspaces and in groups, who had tasks to perform using or assisted by technology. People were now users; design thinking shifted from machine-centric to user-centric (UCD). We began to think of computers as tools to be harnessed, and that technology could empower people to do their task better.

In the PC revolution of the 1990s, collaboration and context became important and observation and participation became key elements of UCD. Understanding users’ work environments would provide greater empathy and enable better designs.

In the 2000s, the Internet and smartphones brought computing into every aspect of our lives, and HCI’s third wave looked beyond the workplace to consider users as unique humans with emotions and culture. Design became about experience[5]. With the shift from run-at-home programs to cloud-based, one-size-fits-all solutions, technologists no longer empower individuals, but service the needs of large userbases in the most efficient, uniform way possible.

Today, options have multiplied. Interfaces are moveable across locations and contexts[5]. We design for experiences that span work, mobile and home domains[6]. Things are messy; “HCI is in the middle of a chaos of multiplicity in terms of technologies, use situations, methods and concepts.”[6]

One popular HCI approach to better fit users’ needs is that of Research through Design (RtD)[38]. RtD uses speculative design explorations to surface unexpected solution and problem areas. Carl DiSalvo’s paper “Designing Speculative Civics” [18] illustrates its various forms:

- The “Division of Domestic Data” project is an imagined user interface for negotiating ownership of digital possessions after divorce.

- The “Data Democracy” project is a prototype web application for exploring public sentiments on civic issues.

- The “Drones for Foraging” project uses technology to aid an existing community to find harvestable fruit.

This paper also illustrates one of the biggest pitfalls in UCD – it is critical to involve involve users during exploration[7]. 1. and 2. were never tested on citizens so we’ve less confidence that the designs will actually empower users. I’d argue that RtD must involve users during or after design to be meaningful. The counter-argument to this is that expert insights are needed to imagine “outside-the-box” solutions and challenge users’ current ways of thinking.

Designing for empowerment clearly requires both innovative thinking from designers and grounded insights from users.

Empowerment through Design and Engagement

This has led to the rise of co-creation and “participatory design“[17, 14]. It is no longer sufficient to study the users, then go away and design something in isolation. Instead the users and the technologists work together in design workshops. Situated design[30] extends this and engages users for longer periods, e.g. [16, 24].

Continuous feedback is key. In software development, this is done through agile development – short iterations where progress is presented to stakeholders each cycle and plans adjusted based on feedback. In startups, terms like “fail fast” and “pivot” embody the idea that it’s crucial to test ideas on users, then adapt quickly.

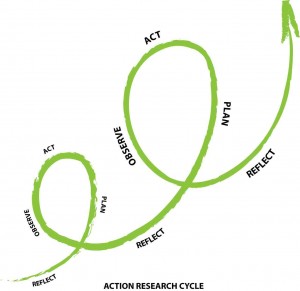

These same principles underly action research[23]. User engagement isn’t a one-off, but a repeated occurrence that impacts the future research path. For me, it’s an essential component of HCI & UCD, and a technique I shall embrace in future research.

Design-after-Design and Expressive Interaction

So, design is key to empowering users. But to empower users, we have to engage in “Design After Design”[13]; a secondary design process that occurs when a designed product is used in unanticipated ways.

We can think of a design as passing some power to the user, whereas empowerment involves users taking some power on their own terms[33]. There’s an inherent conflict between design and empowerment. Designers must allow for adaptation[27] while avoiding prescribed use or feature overload.

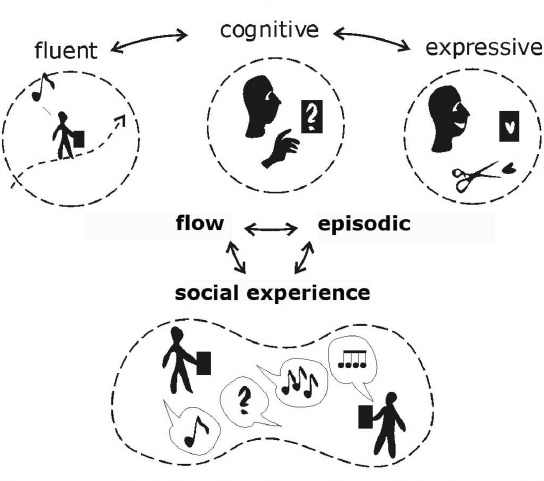

Forlizzi’s model of user interaction[19, 11] is useful here. Product interaction is cognitive when you are aware of the product and think about how to perform the task. Interaction becomes fluent when you lose yourself in the flow of the task and forget the product. Then expressive interaction occurs: you form a relationship with the product through personalisation to adapt the product to your needs.

So to empower, a design must allow for expressive interaction and personalisation.

Empowerment through Data

This has been explored in personal informatics. You can track everything: diet, electricity, exercise, even babies’ toilet habits. By collecting data, and having it presented back to you, you gain valuable insights and are empowered to change your attitudes or behaviour.

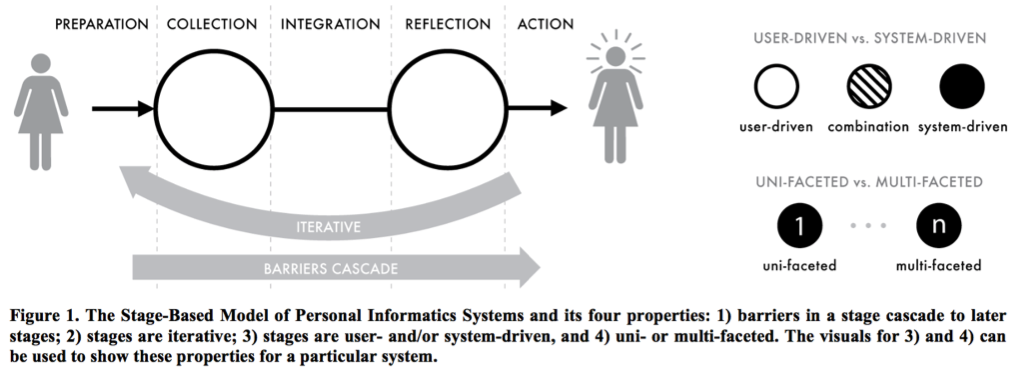

Li et al derived a stage-based model for this[25]:

Empowerment occurs through the latter stages:

- Integration: organise and prepare your collected data for analysis.

- Reflection: analyse and reflect on the information, exploring it and gaining insights.

- Action: act upon on new insights, such as setting new goals or tailoring behaviour.

Systems that enable effective integration, reflection and action are empowering.

In fact, empowerment through data is at the core of an emerging sub-discipline, Human-Data Interaction(HDI). Mortier et al, recognising that we live in a data-driven society, coined this term to emphasise people don’t just have a relationship with computers, but with data itself[28]. They identify three themes in HDI:

- legibility – awareness of data collection, implications of participation.

- agency – ability to act for yourself in a data-based system

- negotiability – ability to understand your data and its implications and act as a result.

Agency in particular will empower users, but high legibility and negotiability matter too.

So, good access to, awareness of, and ability to explore personal data is a critical to empowerment in HCI.

Section 2: Threats to User Empowerment

In this section, I’ll look at the threats to user empowerment that designers should be aware of in today’s complex digital world.

Technology as Magic

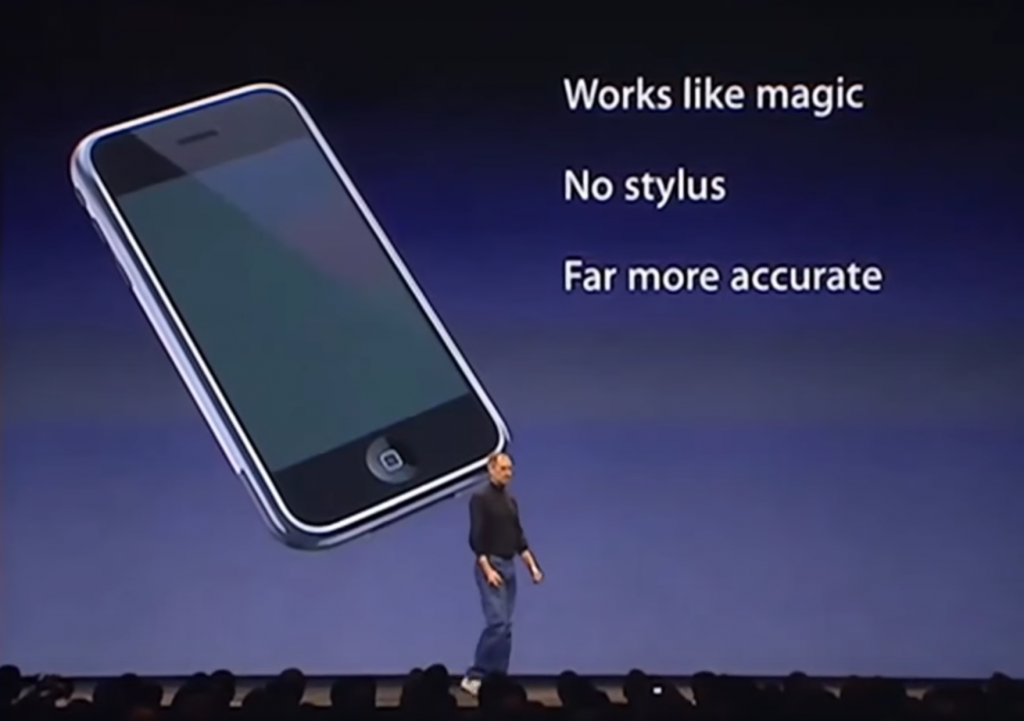

Since we stopped being machine operators who needed to know about their machines, product design has focussed on simplification. In the 90s, more features were desirable; Microsoft Word won by having more features than its competitors. The products that succeed today however, are those that do more for you automatically. If the computer does everything for you don’t need lots of features. Apple’s product strategy over the last few years epitomises this thinking, and regularly uses words like simple and magical. Apple technology “just works“.

To achieve this, hiding the details of technology has become important. If you can seamlessly sync a users’ contacts between their phone, laptop, chat app and email client, then you can simplify the experience dramatically. The problem is that in doing so, you disempower the user. They’re no longer able to control the flow of their information, or to understand what is happening or how they might fix it if something goes wrong.

Companies can reach wider markets through simplification, and this has helped technology go mainstream. Technical skill is no longer needed. But knowledge is empowering, and as they lose understanding of the machines they use, people are disempowered: Thanks to overly simplistic marketing, many don’t know the difference between wi-fi and Internet, which makes it harder for them to diagnose connection issues.

Presenting technology as magical appeals, but disempowers. Entertainment gets confused with tool use[35]. Magical design prioritises “pleasing and surprising a passive user who can only use the solution as authorised“[33].

The Importance of Seams

In 1994, Weiser[35] introduced seams to HCI thinking; the idea that the edges or limits of a product are important to its use. This developed into seamful design[37]. The concept comes from tailoring – the seams of clothing can be unpicked and adapted to your own tastes. For this reason, seams are vital in the hacker and maker spaces[26]. Removing the seams of a product reduces the user’s agency by reducing their ability to adapt the product to their needs. The starkest example is seen in Apple’s hardware designs; in a decade they have systematically removed floppy drives, CD/DVD drives, USB, power and display ports, and now the headphone jack. This supposedly beneficial simplification in reality locks people into Apple’s ecosystem and workflows and completely blocks any possibility for hardware adaptation. It is the antithesis to the original vision of PCs as generally adaptable standardised machines.

Controlling Users Through Opinionated Technology

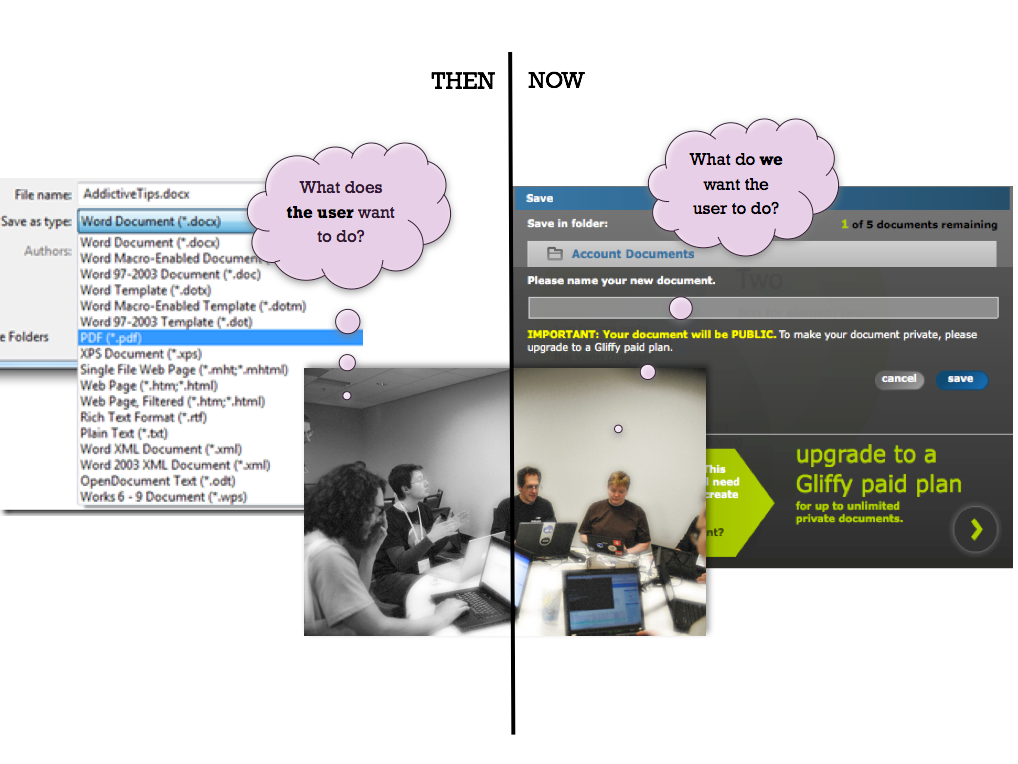

The tech industry has also undergone a paradigm shift in design motivation. When users installed software, they acquired a tool for their own use. Developers provided many features in anticipation of users’ varied needs. But with the move to cloud-based services, the company’s own motivation influences design. In order to scale up to supporting millions of users, design thinking has shifted from “What does the user want to do?” to “What do we want the user to do?”. Design priority has shifted from being useful to being usable[10].

Our products are no longer our own. Increasingly, businesses wish to limit and control the ways in which products are used. In the car industry, engines are becoming black boxes that people cannot repair without professional assistance. DRM technology limits the playability and portability of digital audio and video files – as Gillespie et al[21] write:

Not only is the technology being designed to limit use, but to frustrate the agency of its users. It represents an effort to keep users outside of the technology, to urge them to be docile consumers who ‘use as directed’ rather than adopting a more active, inquisitive posture towards their tools.

This type of deliberately seamless design can be considered opinionated, purposefully hiding the seams from users to limit their agency.

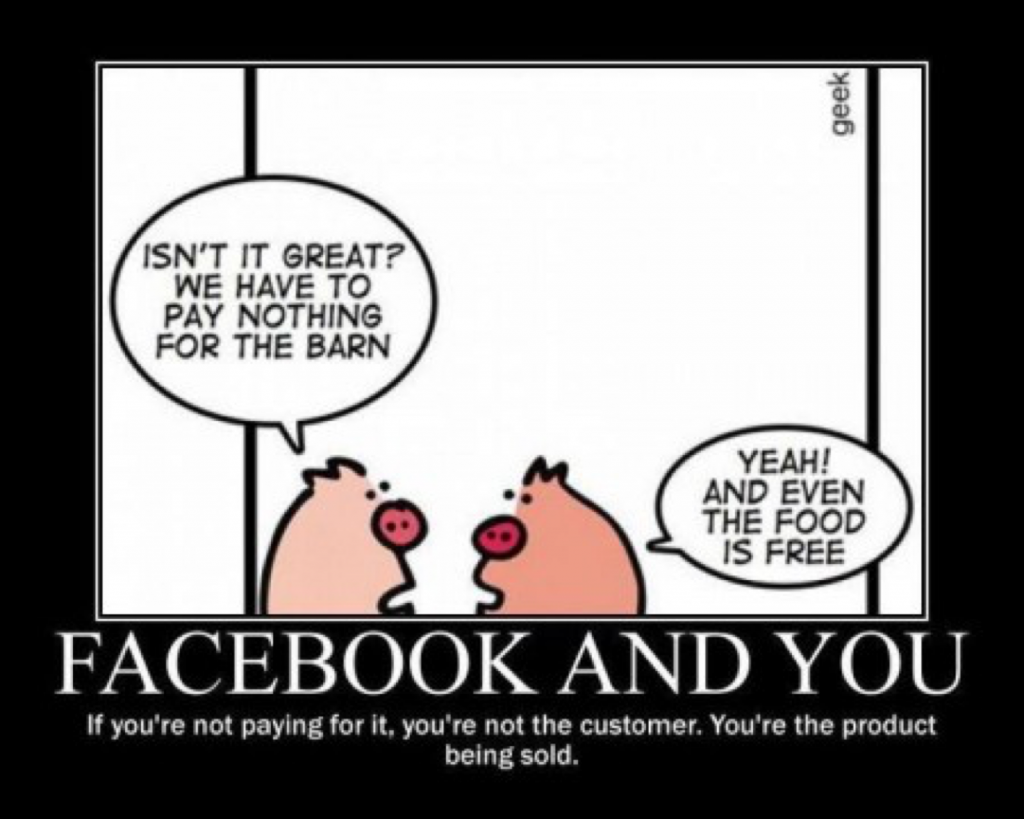

The cost of “free”: Closed Ecosystems

Why have companies stopped putting the user first? Internet economics provides the answer. Since the early days of the commercial Internet, people have expected Internet content to be free. In reality, nothing is truly free. Companies have sought alternative revenue sources, and have settled upon advertising and service subscriptions.

These both rely on “keeping” the user locked in to their ecosystem. Companies want to maximise ad views, which means getting users to use their portal rather than someone else’s. And once subscribed, companies are motivated to make it hard and undesirable for users to leave for another service, which encourages them to limit data portability, and close the seams. Twitter recently closed its APIs (upon which many useful applications were built) to protect their business.

Both models push companies towards creating “one-stop shops” – full ecosystems of services and products which offer a “complete” experience. This too, harms user autonomy because users can no longer afford to mix-and-match solutions from different providers according to their strengths – as they might with hi-fi separates. Users face a Hobson’s choice of paying multiple providers or “making do” with the limitations of a single service offering. Customers of Netflix or Spotify have more limited choices than when they bought discs.

This has created the Splinternet, a messy digital world where users have invested money and data in a plethora of different services, and have very little agency to simplify their experience. Worse still, each provider builds their ecosystem as if the others do not exist – which is why families can now end up with at multiple representations of their family’s online access, each with its own logins, payment systems and preferences: Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Netflix and Spotify.

As we can see, the Internet is now wired against user empowerment.

Who will protect users’ freedoms?

Now that we understand these forces against users’ interests, we must ask, what can be done? Who should act? HCI practitioners have always been “advocates for user interests within system design”[15]. HCI faces an internal conflict, as commercial HCI practitioners will have to sacrifice user empowerment for commercial reasons, whilst those in academia can put users’ interests first, and design solutions that empower users, but with no ability to bring them to market.

Users’ disempowerment is often invisible to them. Due to a lack of legibility[28], users may be unaware of the missing seams on their products, and may not realise how trapped their data is or how locked in they are until they try to leave. Therefore we can no longer rely on participatory approaches to uncover this particular type of user need, leaving a tricky tightrope to walk, since we’ve grown used to the idea that working with users is sufficient and necessary to uncover their needs. Nonetheless, we must be wary of thinking “we know best”.

With no other advocates looking at the big picture of user empowerment in design, it must fall to hackers, makers, power users, digital rights activists and HCI researchers to fight this corner on behalf of the users.

Section 3: A new HCI Challenge: Designing for Autonomy

This brings me to my conclusion, which is to outline the the next grand challenge for HCI and Digital Civics. I believe this is the key question that will help bring us from the third wave to the fourth wave of HCI:

How do we rebalance power and empower users to have true autonomy?

To be considered autonomous, people must be free to use computing devices, software and services in the ways that suit them. They must be free to switch providers without loss of data or capability, and should be able to adapt products to their needs.

Here are four areas of focus which may help us find the solution:

1) Holistic Design and Ubicomp

Back in 2006, Bødker highlighted the lack of commitment of designers to users, and said that she didn’t believe we will get “towards a true third wave… until we embrace people’s whole lives“[5]. The field of ubiquitous computing (ubicomp) has begun to move beyond device-centricity. Abowd says we need to shift from “programming environments to programming environments“[1, 8]. Building on Weiser’s prophetic ubicomp vision[34], he frames computing as something that cannot be designed for a single screen or device, only for the totality of the human experience. The Internet of Things and cloud computing offer the means to achieve this vision. Some tangible computing[9] projects[22] give a glimpse into this future.

2) The Semantic Web and Open Data

The Semantic Web[4] is a vision of a web where computers understand data enough to connect related concepts and entities in a format-agnostic, language-agnostic way. Today, hyperlinks are dumb. Our files are meaningless blobs to the computer that need to die[12]. Open knowledge graphs such as Freebase (superseded by Wikidata) provide a framework we can harness in building computing systems that bridge Internet silos.

3) Personal Data Lockers and Pull vs Push

Siegel’s vision[29 and video below] imagines an Internet turned “inside-out”. Companies would pull our data, instead of us pushing it to them[32]. We’d control our own data and license it to organisations for specific purposes. This radically rethinks how Internet businesses work today – but could provide a blueprint for future user-empowered designs while still offering business benefits.

4) Agonistic Technologies to Encourage Reflection

Agonism[17] is a political technique for challenging the status quo from the outside. It’s been applied to HCI design, to provoke users into questioning things they normally take for granted: Gaver and others have created ambiguous[31] or provocative[20] designs that start conversations about the way things are. Given this and an effective Human-Data Interface to enable reflection, people could gain awareness of missing seams and lost agency and demand more adaptable products.

In Summary

I’ve shown that while in HCI we’ve continued to strive to better understand and empower users and increase their agency, commercial technology has been working against them, with user problems being “solved” in increasingly fractured and provider-centric ways. The most pressing challenge for HCI and Digital Civics is the question of how we can restore the balance of power and empower users to harness computers as tools.

As HCI practitioners we must advocate for user freedom as never before. We must think differently about the way we help users. We can’t empower them through the commercial directives of employers. We must design systems that minimize barriers, maximize flow, and above all, enable people to adapt their usage, in a way that fits their life. It is not clear how this will happen, but it’s clear that it must, if computers are to be truly useful to people.

Computers are supposed to be tools to make our lives easier.

Technology should serve us above all else.

Total length (excluding Sources & this line): 2,999 words

Sources

[1] Abowd, Gregory D. “What next, ubicomp?: celebrating an intellectual disappearing act.” Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Ubiquitous Computing. ACM, 2012. [ACM link]

[2] Bannon, Liam. “From human factors to human actors: The role of psychology and human-computer interaction studies in system design.” Design at work: Cooperative design of computer systems 25 (1991): 44. [ResearchGate PDF link]

[3] Bell, Gordon, and Jim Gemmell. Your life, uploaded: The digital way to better memory, health, and productivity. Penguin, 2010. [Google Books link]

[4] Berners-Lee, Tim, Mark Fischetti, and Michael L. Foreword By-Dertouzos. Weaving the Web: The original design and ultimate destiny of the World Wide Web by its inventor. HarperInformation, 2000. [Google Books link]

[5] Bødker, Susanne. “When second wave HCI meets third wave challenges.” Proceedings of the 4th Nordic conference on Human-computer interaction: changing roles. ACM, 2006. [ACM link]

[6] Bødker, Susanne. “Third-wave HCI, 10 years later—participation and sharing.” interactions 22.5 (2015): 24-31. [ACM HTML link]

[7] Bowyer, Alex. “Imagining the Future: Speculative Civics”. Blog post, HCI for Digital Civics 2016, Open Lab. [link to blog post]

[8] Bowyer, Alex. “The Future of Computing is Programming for Individuals in their Environments”. Blog post, HCI for Digital Civics 2016, Open Lab. [link to blog post]

[9] Bowyer, Alex. Tangible Computing: Data You Can Touch. Blog post, HCI for Digital Civics 2016, Open Lab. [Blog post link]

[10] Bowyer, Alex. “Useful Computing: Reclaiming a Lost Vision”. Blog post, HCI for Digital Civics 2016, Open Lab. [link to blog post]

[11] Bowyer, Alex. What is Experience anyway? Blog post, HCI for Digital Civics 2016, Open Lab. [Blog post link]

[12] Bowyer, Alex. Why files need to die. Published article, O’Reilly Radar [O’Reilly link]

[13] Björgvinsson, Erling, Pelle Ehn, and Per-Anders Hillgren. “Design things and design thinking: Contemporary participatory design challenges.” Design Issues 28.3 (2012): 101-116. [MIT Press link]

[14] Björgvinsson, Erling, Pelle Ehn, and Per-Anders Hillgren. “Participatory design and democratizing innovation.” Proceedings of the 11th Biennial participatory design conference. ACM, 2010. [ACM link]

[15] Cooper, Geoff, and John Bowers. “Representing the user: Notes on the disciplinary rhetoric of human-computer interaction.” Cambridge Series On Human Computer Interaction (1995): 48-66. [Google Books link]

[16] Crivellaro, Clara, et al. “Re-Making Places: HCI,’Community Building’and Change.” Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, 2016. [ACM link]

[17] DiSalvo, Carl. “Design, democracy and agonistic pluralism.” Proceedings of the design research society conference. 2010. [link]

[18] DiSalvo, Carl, Tom Jenkins, and Thomas Lodato. “Designing Speculative Civics.” Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, 2016. [link to PDF at co-author’s site]

[19] Forlizzi, Jodi, and Katja Battarbee. “Understanding experience in interactive systems.” Proceedings of the 5th conference on Designing interactive systems: processes, practices, methods, and techniques. ACM, 2004. [ACM link]

[20] Gaver, William, et al. “The Datacatcher: Batch Deployment and Documentation of 130 Location-Aware, Mobile Devices That Put Sociopolitically-Relevant Big Data in People’s Hands: Polyphonic Interpretation at Scale.” Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, 2016. [ACM link]

[21] Gillespie, Tarleton. “Designed to ‘effectively frustrate’: copyright, technology and the agency of users.” New Media & Society 8.4 (2006): 651-669. [SAGEpub link]

[22] Güldenpfennig, Florian, Daniel Dudo, and Peter Purgathofer. “Toward Thingy Oriented Programming: Recording Macros With Tangibles.” Proceedings of the TEI’16: Tenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction. ACM, 2016. [ACM link]

[23] Hayes, Gillian R. “The relationship of action research to human-computer interaction.” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI)18.3 (2011): 15. [ACM link]

[24] Kazakos, Konstantinos, et al. “A Real-Time IVR Platform for Community Radio.” Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, 2016. [ACM link]

[25] Li, Ian, Anind Dey, and Jodi Forlizzi. “A stage-based model of personal informatics systems.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, 2010. [ACM link]

[26] Meissner, Janis. “Empowerment through Making?”. Blog post, HCI for Digital Civics 2015, Open Lab. [link to blog post]

[27] Moran, Thomas P. “Everyday adaptive design.” Proceedings of the 4th conference on Designing interactive systems: processes, practices, methods, and techniques. ACM, 2002.

[28] Mortier, Richard, et al. “Human-data interaction: the human face of the data-driven society.” Available at SSRN 2508051 (2014). [SSRN link]

[29] Siegel, David. Personal Data Locker Vision Video, 2010 [Vimeo link]

[30] Simonsen, Jesper, et al. Situated design methods. MIT Press, 2014. [Google Books link]

[31] Sengers, Phoebe, and Gaver, Bill. “Staying open to interpretation: engaging multiple meanings in design and evaluation.” Proceedings of the 6th conference on Designing Interactive systems. ACM, 2006. [ACM link]

[32] Siegel, David. Pull: The power of the semantic web to transform your business. Penguin, 2009. [Google Books link]

[33] Storni, Cristiano. “The Problem of De-sign as conjuring: Empowerment-in-use and the politics of seams.” Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference: Research Papers-Volume 1. ACM, 2014. [ACM link]

[34] Weiser, Mark. “The computer for the 21st century.” Scientific american 265.3 (1991): 94-104. [ACM link]

[35] Weiser, Mark. “Creating the invisible interface:(invited talk).” Proceedings of the 7th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and technology. ACM, 1994. [ACM link]

[36] Weiser, Mark, and John Seely Brown. “The coming age of calm technology.” Beyond calculation. Springer New York, 1997. 75-85. [link on Weiser’s site]

[37] Wenneling, Oskar. “Seamful Design–The Other Way Around.” [PSU PDF link]

[39] Zimmerman, John, Jodi Forlizzi, and Shelley Evenson. “Research through design as a method for interaction design research in HCI.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems. ACM, 2007. [ACM link]

[39] “There’s an app for that”. iPhone 3G commercial, Apple, 2009. [YouTube link]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply